Written by Paul Bardea, Tammy Liu, Abhishek Madan, Andrew McBurney, and Dave Pagurek van Mossel

We present a likelihood function for Sequential Monte Carlo sampling that lets artists draw guiding curves to control the output of generating grammars. This framework enables the high-level structure of models to be intuitively specified while allowing for sufficient variation in the low-level details. Our method can be computed at interactive rates to enable the short feedback loops required for exploratory design.

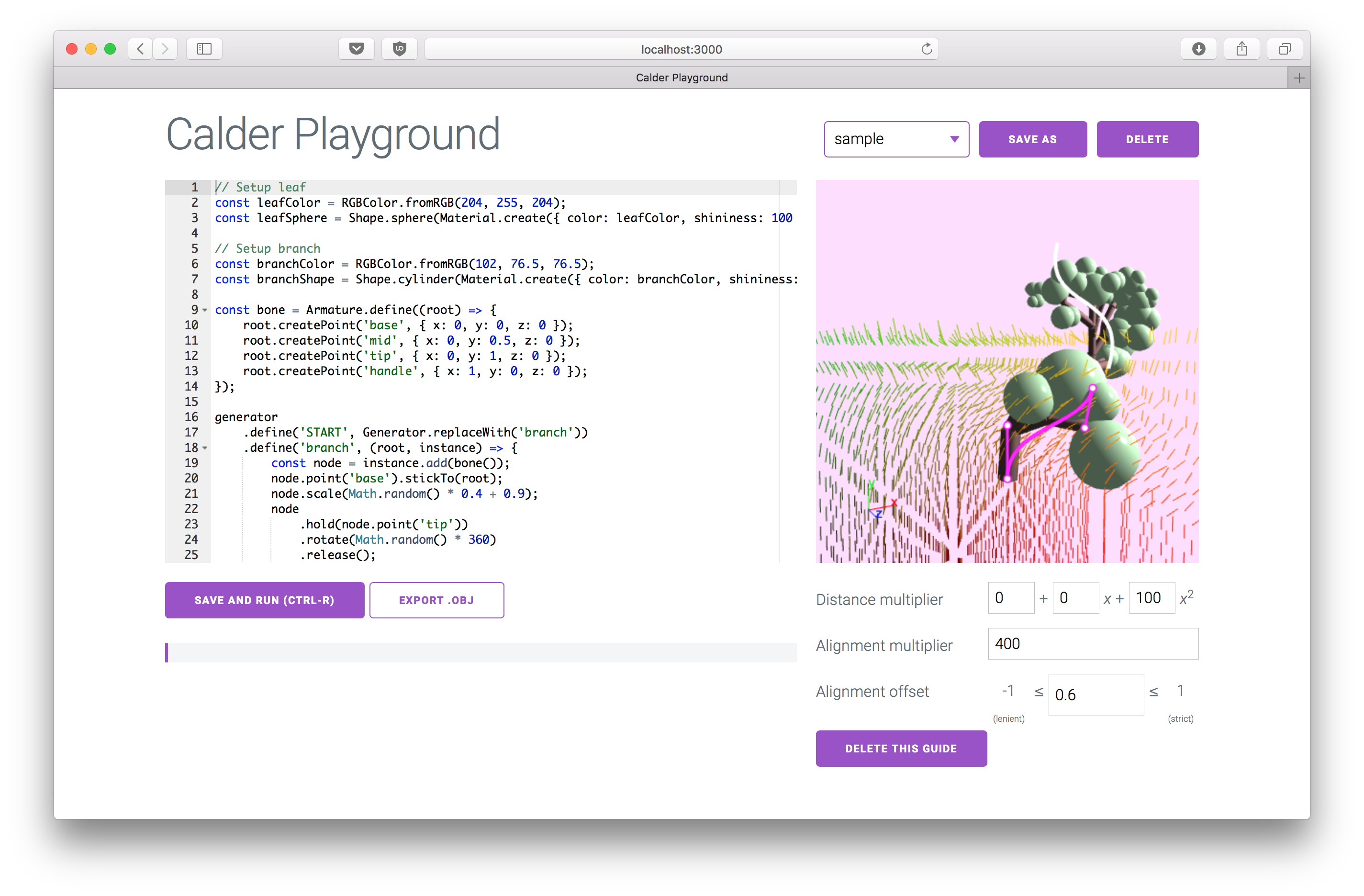

We additionally created a proof-of-concept editor that uses this method to enable real-time searching of models produced by a grammar to demonstrate this capability.

|

| The guiding curves editor, with a pane on the left to create a generating grammar, and a pane on the right to draw guiding curves. |

Procedural modelling is a great way to add a level of detail and richness to 3D modelling that would be impractical to create by hand. It is used, for example, to apply patterns to large scales to create whole landscapes, or on a smaller scale to create varied individual plants and creatures.

Grammars are a convenient way to express those patterns. Unfortunately, they produce a broader space of models than would be artistically desirable. For each good model produced, there may also be a weird one. Editing the grammar to prevent this is extremely hard (consider trying to modify the English grammar to prevent gross sentences from being valid for a sense of how hard this can be.)

An alternative is to search the space of models produced by a grammar for samples that best fit a set of constraints. You can think of the constraint search as controlling the growth of generative models. Past work has used probabilistic inference to do the search and has provided constraints on properties such as the volume a model occupies and the shape of its shadow. However, it takes a lot of effort to create targets for these constraints, and they take tens of seconds to run a search on. This prevents artists from working iteratively, where there is a quick feedback loop between the artist and the tool. Ideally, we would have a workflow where the artist makes changes, looks at interactive feedback, and uses that to make more changes. This sort of feedback requires the search to run in under a second. This work aims to do as much useful work for the artist as possible in under a second to enable iterative design.

We created an editor that lets you write a grammar and then explore the space of models generated by the grammar by drawing guiding curves.

|

| Demonstration of editing guiding curves and getting real-time feedback. |

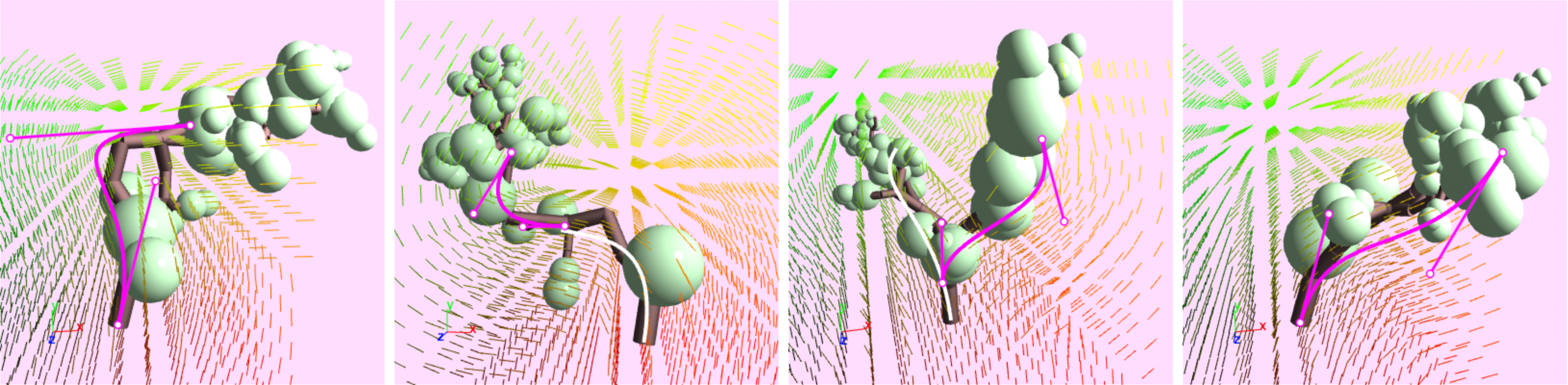

When we generate a model, we start by just constructing a skeleton of the model. Curves are used to assign a cost to "bones" of the skeleton, and we run optimization to find a skeleton with the lowest total cost. We then turn the skeleton into an actual model by adding final geometry to the bones.

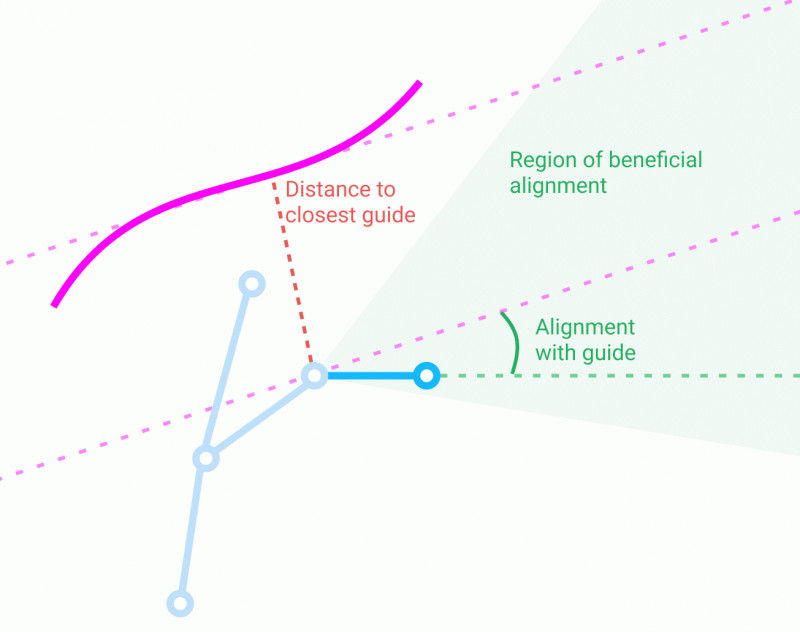

For each bone, there are two factors affecting the cost:

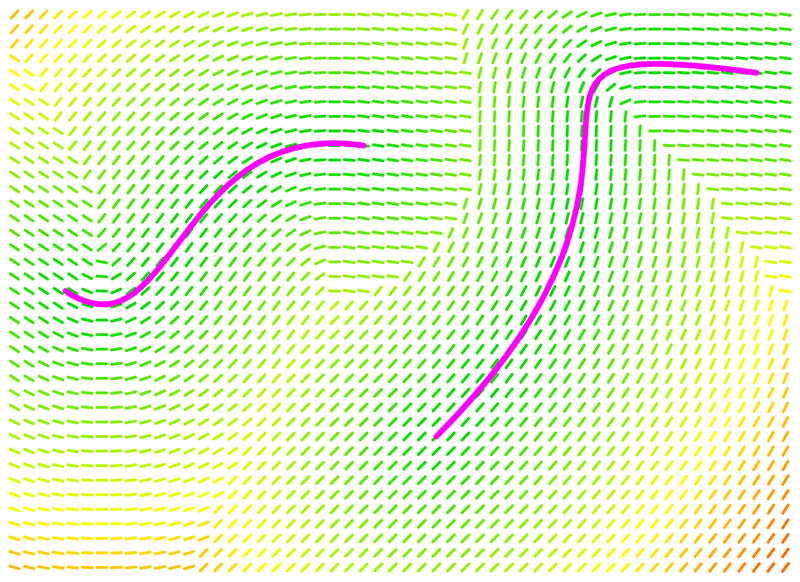

- Alignment to a vector field. We find the closest point on a guiding curve to the base of the bone and see how closely the direction of the bone aligns with the gradient of the curve at the closest point. Well-aligned bones have a negative cost, incentivizing adding well-aligned bones; poorly-aligned bones have a positive cost. How well-aligned a bone needs to be to have a negative cost is a tunable parameter.

- Distance to the guiding curve. When we find the closest guiding curve, we add a cost based on how far away the bone is to balance the alignment cost. You can pick if you want the cost to scale linearly or quadratically with distance.

|

|

| The information the cost function operates on when adding a new bone. | The alignments for each point in space around some guides, coloured to represent the distance cost for that location. |

Normally, we find an optimal model by taking a generation of partially generated models, and then seeding the next generation from the previous generation proportional to how good their costs look so far. To get better final results, we want the samples we pick to be as likely as possible to have a good cost when they are fully generated.

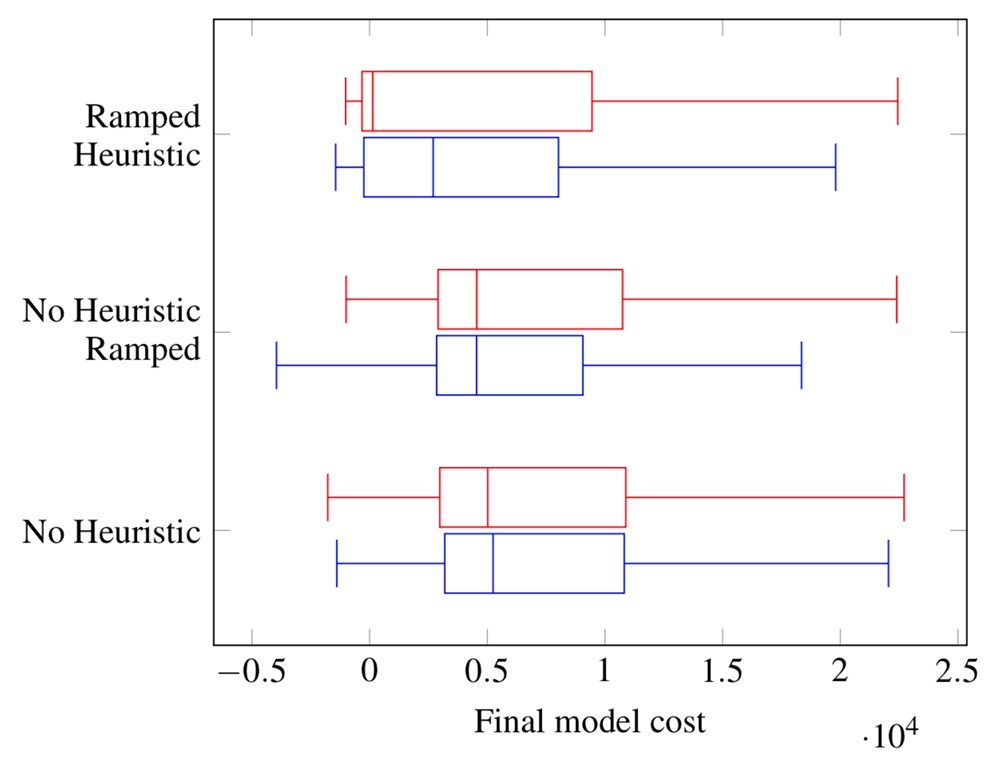

To help with this, for every type of component that a grammar can have, we sample the components generated by it and find the general direction they tend to grow in. In the early generations when models are the most incomplete, we add alignment costs for these expected directions to the total cost under the assumption that it gives a more accurate picture of what a sample's final cost might look like. As we get more and more complete models in successive generations, we lower the weight of the expected direction costs, ramping the weight down eventually to zero. We also ramp down the number of models in each generation. We found that this helps find lower-cost final models more consistently than we would without this estimation under the same time constraints.

|

| A comparison of final model cost distributions with and without using heuristic costs in a time limit of 200ms. Alignment offsets of 0.6 and 0.5 were used, respectively. |

yarn installyarn testTo generate the examples files (under /examples), run:

yarn webpackTo add a new example:

- Add the example typescript file in

/src/examples - Add the typescript file as an entrypoint in

webpack.config.js - Create a new HTML file in

/examples

Run the autoformatter on your code:

yarn fix-formatCalder was named in honor of Alexander Calder, the American sculptor who is known for using wire to construct three-dimensional abstract line drawings of various kinds of objects. The organization's image is an illustration of Calder's 1934 piece titled Red and Yellow Vane.

"To an engineer, good enough means perfect. With an artist, there's no such thing as perfect." — Alexander Calder