forked from atmcgrath/reactor-jct

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 0

Commit

This commit does not belong to any branch on this repository, and may belong to a fork outside of the repository.

moving science page to directory structure

- Loading branch information

Showing

1 changed file

with

105 additions

and

0 deletions.

There are no files selected for viewing

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| Original file line number | Diff line number | Diff line change |

|---|---|---|

| @@ -0,0 +1,105 @@ | ||

| .ve-style ./assets/custom.css | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| .ve-header "The Science Behind Nuclear Power" wc:NSC-Oct-2017.jpg sticky logo=https://digbmc.github.io/reactor-jct/favicon.ico url=# | ||

| - [Home](/) | ||

| - [History](nuclear-history/) | ||

| - [Science](science/) | ||

| - [Disasters](nuclear-disasters/) | ||

| - [Present and Future](present-and-future/) | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ### How Nuclear Energy is Generated | ||

|

|

||

| .ve-media wc:Liquid_drop_model_of_nuclear_fission.jpg right static | ||

|

|

||

| The first law of thermodynamics asserts that heat is energy, which is generated in the process of nuclear fission. The purpose of nuclear reactors is to house this process in order to reap its energy output. Fission occurs when a neutron hits a larger atom's nucleus which is split into two smaller atoms and some neutrons. The neutrons created from the split can then generate a chain reaction by hitting other large atoms and so on. In the case of most nuclear reactors, the fuel of choice is uranium, which acts as the large atom in nuclear fission. Uranium is used because its atoms easily split apart, it is easy to initiate and control, and it is abundant on Earth. [^1] | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ### The Process of Nuclear Energy Production | ||

|

|

||

| First, uranium is processed and enriched at a uranium mill in order to increase the concentration of uranium atoms. Then it is pressed into little uranium pellets which are packed into long metal rods called fuel rods.[^1] The fuel rods are grouped together to make a fuel assembly. The process of nuclear fission starts generating heat in the fuel assembly. The heat generated boils water which is located either in the same compartment or in a separate location. The location of the water is determined by the kind of reactor in use. The boiling water turns to steam which spins an electricity-generating turbine. The steam is then condensed and the water gets recycled once more. The process is controlled by control rods which absorb extra neutrons in order to slow down or stop the reaction. Control rods are made from neutron-absorbing materials such as boron and silver, which aid in the hindering of neutrons which continue the nuclear fission chain reaction. One can moderate the speed and ability to generate energy by inserting the control rods for a certain length or removing them entirely. | ||

|

|

||

| ### Types of Reactors {.cards} | ||

|

|

||

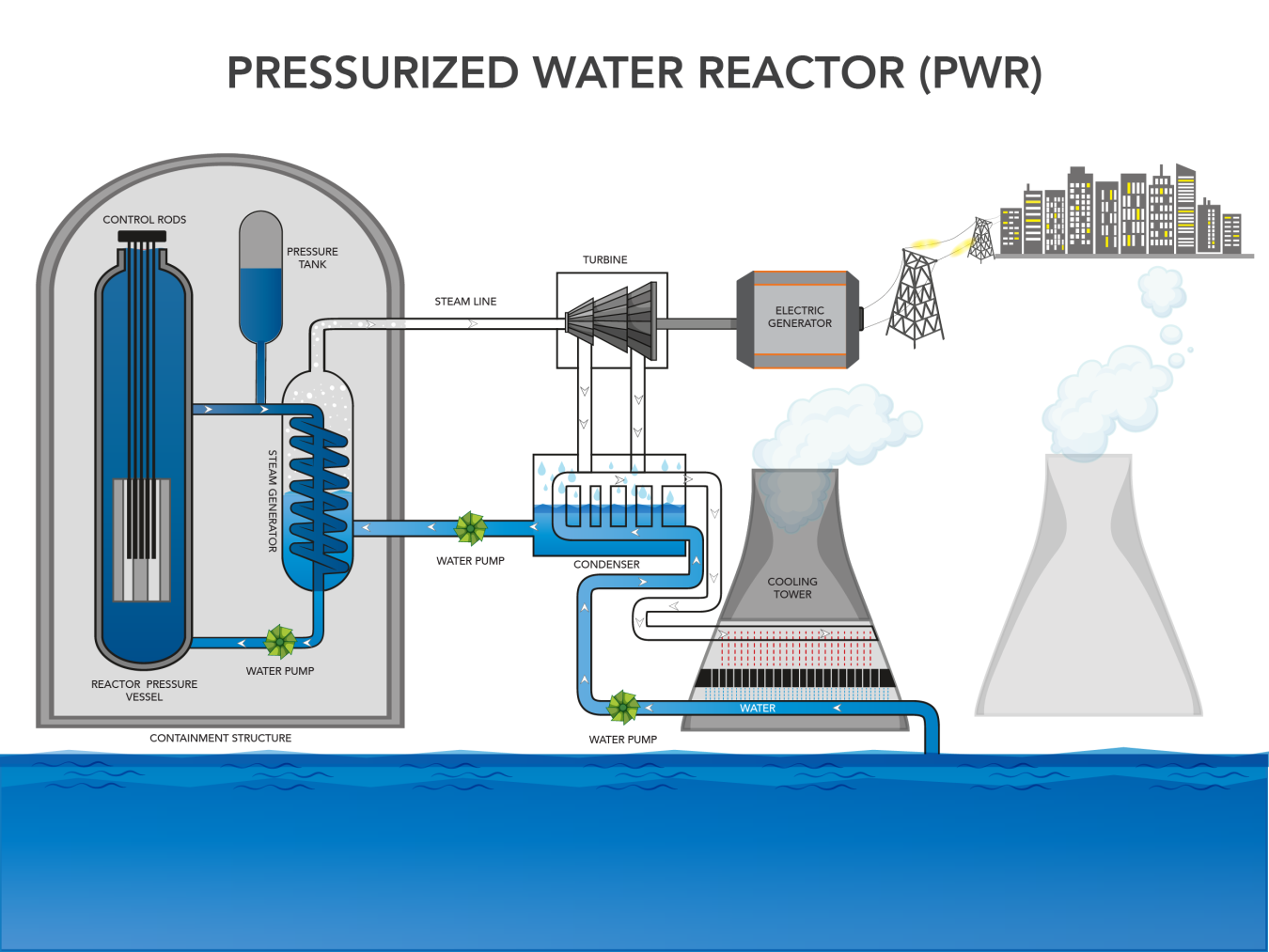

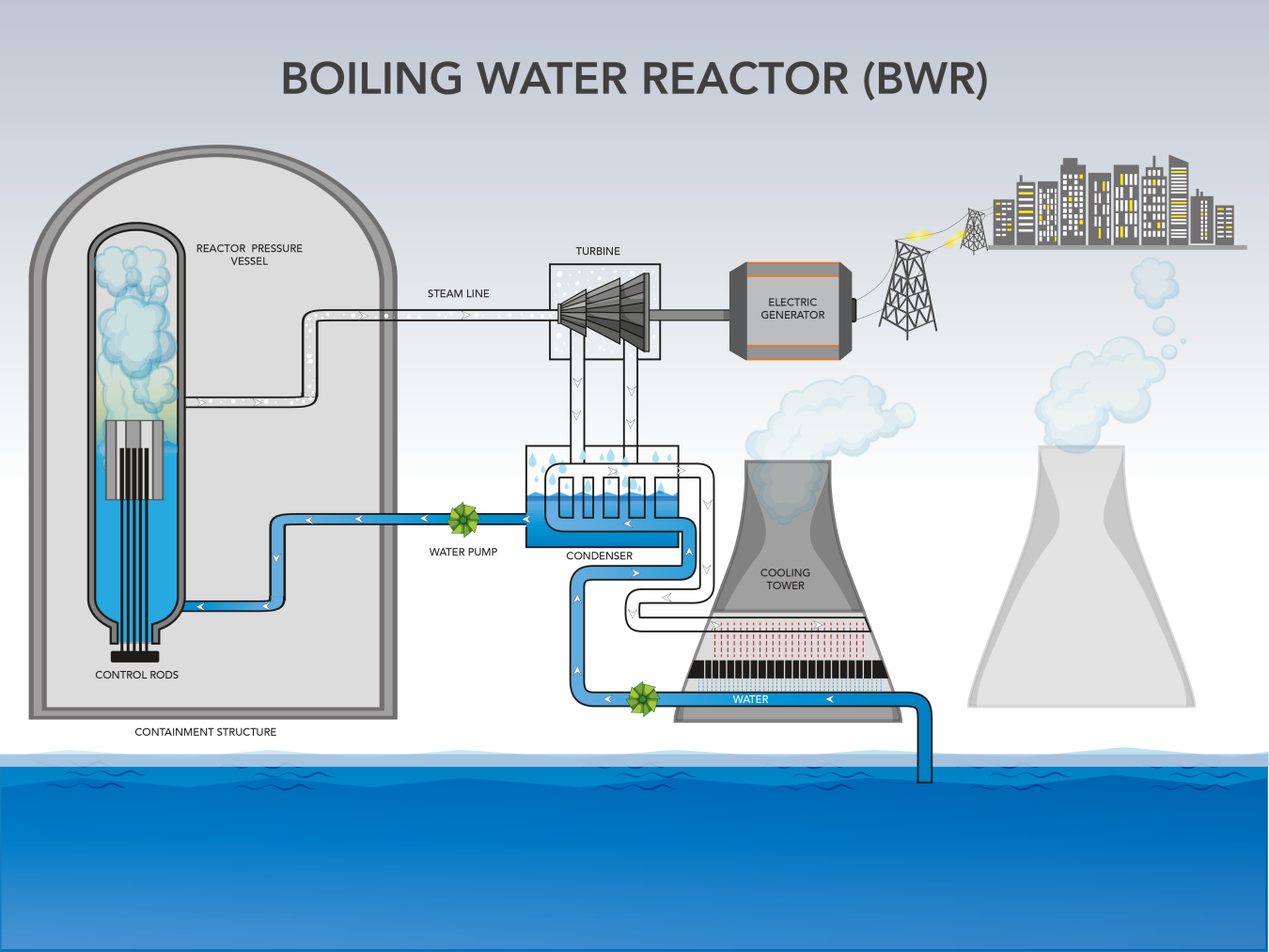

| There are two kinds of nuclear reactor designs currently used in the United States, and their main difference is the way they generate steam. One of them is the more common pressurized water reactor. This kind of reactor uses water for cooling the reactor and for driving the electricity-generating turbines; however, those processes are separated via loops and do not mix. The other reactor is the less common boiling water reactor. This reactor uses the same water which is used to cool and power the electricity-generating turbines. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| #### Pressurized Water Reactor | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| Water is heated by the nuclear reactor and kept under high pressure. Afterward, it is transformed into steam by a steam generator which is used in the electric turbine.[^2] | ||

|

|

||

| #### Boiling Water Reactor | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| Water is heated by the nuclear reactor. The boiling temperatures produce steam which would then be used for electricity generation.[^2] | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ### The Chornobyl Reactor {.cards} | ||

|

|

||

| The previous two reactors were moderated and cooled by water, which means that the water slows down the neutrons used in nuclear fission. The type of reactor that was used in Chornobyl is an RBMK, a high-power channel reactor. This kind of reactor is cooled by water but controlled by graphite moderators. This means that the control rods, which were made from boron with graphite tips on the ends, were used for slowing down neutrons in the reactor core. This reactor was created with several factors taken into account, mostly to save on costs. The first factor was that the fabrication of RBMK parts can be done at existing manufacturing plants, which would save money by not having to build new factories for parts. The energy output was also very important since most of the Soviet Union relied on nuclear energy for cheaper electricity, so the RBMK reactor had no upper power limits. The RBMK was considered to have a state-of-the-art safety protocol, with more than 1000 primary circuits which would increase the safety of the reactor system. Lastly, the fuel itself was highly efficient as it was able to use slightly less enriched uranium than in other common reactors which saved money.[^3] | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| #### RMBK Reactor | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| The RMBK diagram showing its complex construction.[^4] | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ### The Reactor Explosion | ||

|

|

||

| The explosion started when there was too much power generated and the heat from the power increased, which made the fuel rods break and leak into the external cooling system. When coming into contact with the cooling system without the protection of the control rods, the water elementally separated which blew the lid off the reactor. This hot steam explosion set off a chain of events that led to the graphite of the control rods melting. When mixed with other elements such as nuclear fuel and fission products, the melted graphite created corium, which then turned into a lava-like radioactive substance which is extremely dangerous. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Some say that the Chornobyl reactor was doomed to fail due to the numerous design flaws in its creation. The first issue was that the reactor had a positive void coefficient. This means that when there is an increase of steam in the core or a "void" of neutron-absorbing water, the reactivity of the reactor will increase. Comparatively, boiling water or pressurized water-style reactors would have a negative void coefficient, which will decrease reactivity with an increase of steam in the core. This provides an extra level of safety and support for the security of the reactor. The second issue is that there was a way for the operators to manually override the emergency protocol. This creates an issue of human error, whereas if there was no way to override it and the safety protocol was in place it would be more safe without human interference. Lastly, the control rods took a long time to come into position—18 seconds. While 18 seconds does not seem like much, this timing has now been changed to 12 seconds, and the extra six seconds could make a difference between life and death. [^4] | ||

| For more information on the design flaw topic: [Cutting Corners](https://digitalscholarship.brynmawr.edu/reactor-room/projects/cutting-corners/) | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ### The Post-Chornobyl Changes | ||

|

|

||

| In order to prevent further accidents, there were some modifications done to the reactor design for the health and safety of the operators and those in the surrounding area. The first was the reduction of the void coefficient of reactivity. In order to do that, the design was changed in three ways: 80-90 new neutron absorbers were installed in the core to inhibit operation at low power; the amount of control rods was increased from 26-30 rods to 43-48 rods; and fuel enrichment was increased from 2% to 2.4%. The second large modification was the improvement of the response efficiency of the emergency protection system. A fast-acting emergency protection system, FAEP, was installed which rapidly introduced negative reactivity. The third modification was the introduction of calculation programs to provide an indication of the value of the effective number of control rods remaining in the core in the control room so that the operators would make decisions based on recent and correct data. Finally, measures were introduced to prevent operators from bypassing the emergency safety systems while the reactor is active. All of these design changes were necessary for the safety and security of the reactor and its operators. [^5] | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ## Further Reading {.cards} | ||

|

|

||

| ### Accidents & Disasters {href="/nuclear-disasters"} | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| *A representative survey of nuclear incidents.* | ||

|

|

||

| ### Present & Future {href="/present-and-future"} | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| *The present state and predicted future of nuclear energy.* | ||

|

|

||

| ### Nuclear History {href="/nuclear-history"} | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| *The history of nuclear technology from 1930s to the 1980s.* | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ### Reactor Room Project {href=https://digitalscholarship.brynmawr.edu/reactor-room/} | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| *Return to main page.* | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| [^1]: "How Does a Nuclear Reactor Work" [https://world-nuclear.org/nuclear-essentials/how-does-a-nuclear-reactor-work.aspx](https://world-nuclear.org/nuclear-essentials/how-does-a-nuclear-reactor-work.aspx) Accessed 12 June 2023. | ||

| [^2]: Graphics made by Sarah Harman | [https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/nuclear-101-how-does-nuclear-reactor-work](https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/nuclear-101-how-does-nuclear-reactor-work) | ||

| [^3]: Semenov, B. A. “Nuclear Power in the Soviet Union.” *IAEA Bulletin*, vol. 25, no. 2, 1983. | ||

| [^4]: Kirk, Benny. “37 Years After Chernobyl, RBMK Reactors Are Still Operating in Russia.” *Autoevolution*, 20 Feb. 2023.[https://www.autoevolution.com/news/37-years-after-chernobyl-rbmk-nuclear-reactors-are-still-operating-in-russia](https://www.autoevolution.com/news/37-years-after-chernobyl-rbmk-nuclear-reactors-are-still-operating-in-russia-210581.html#:~:text=But%20if%20you%20thought%20RBMKs,eight%20are%20still%20in%20operation) | ||

| [^5]: World Nuclear Association. "RBMK Reactors | Reactor Bolshoy Moshchnosty Kanalny | Positive Void Coefficient". - World Nuclear Association. 1991, [https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/nuclear-power-reactors/appendices/rbmk-reactors.aspx](https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/nuclear-power-reactors/appendices/rbmk-reactors.aspx) |