.center[

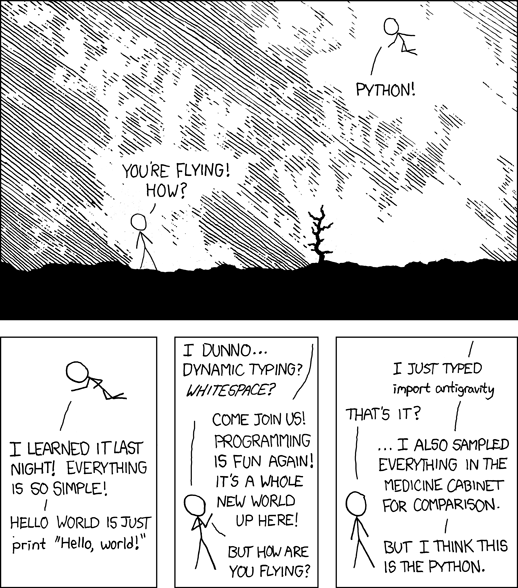

Let's learn some basics of python in 60 minutes.

We'll assume you already have python 2.7 installed. The code here should work in 3.x as well. There are some differences which can break your code if you use the wrong version.

The python command starts the python interpreter.

bash$ pythonYou will see the following prompt:

.hljs[

Python 2.7.12 (default, Oct 11 2016, 05:24:00)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 8.0.0 (clang-800.0.38)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

]

--

Now try telling python to do something:

>>> print("hello world")

hello world

>>>This is a simple python script, which we'll save as tut1.py:

#!/usr/bin/env python

print("hello world")--

Make the script executable:

bash$ chmod +x tut1.py

bash$--

Run the script from the command prompt:

bash$ ./tut1.py

hello world

bash$--

You have just written and executed your first python program!

You create a variable just by assigning to it. No var or other instantiation keywords. No declaration, just assign.

x = 7

y = "foo"

pi = 3.14159265Integers:

x = 10

y = 3

print(x/y) # prints 3 (python 2.7)

# prints 3.3333333333333335 (python 3)Notice that integer division gives you an integer in 2.7, but a float in 3.x.

--

Floating Point:

x = 3.14159265

y = 7

print(x/y) # prints 0.44879895000000003Blocks are defined in python by indenting the code.

The if statement executes the indented code block if the condition

evaluates to True:

if condition:

statement

elif condition:

statement

else:

statement--

Another form of if is the ternary operator:

y = 7

x = 5 if y>1 else 10 # x is now equal to 5The for loop iterates over a sequence:

for name in [ "bob", "sam", "ben", "sue", "bev" ]:

print(name)--

You can use the range function to use a numeric counter:

for i in range(10):

print(i) # prints 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9--

The while loop iterates as long as a condition is true:

i = 0

while i < 10:

print(i)

i = i+1The continue statement skips to the next iteration of the loop and

continues looping:

for i in range(1, 11):

if i == 3:

continue

print(i) # prints 1 2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10--

The break statement skips out of the loop without executing any more

iterations.

for i in range(10):

if i == 3:

break

print(i) # prints 0 1 2The else is not just used after if, but can follow a loop:

for i in range(10):

pass # this statement does nothing! use it as a placeholder

else:

print("else")--

The else block is only executed after the loop condition evaluates

as False, but not following a break:

for i in range(10):

if i == 3:

break

else:

print("else") # this line is skipped

print("done") # prints "done"There are six sequence types in python: str, unicode, list, tuple, buffer, xrange. We are going to talk about str, list, tuple.

--

Access elements of a sequence (such as a string) using brackets. The indexes start with zero:

x = "bar"

print(x[0]) # b

print(x[1]) # a

print(x[2]) # rThis may look familiar like arrays in other languages.

--

Strings are written using single or double quotes. Strings with double quotes can contain apostrophes or single quotes. Strings with single quotes can contain double quotes.

x = "this is a test"

print( len(x) ) # prints 14

print( x[10] ) # prints t

y = "we're home!"

z = 'sam says "hi"'Lists are constructed with brackets and every element should be the same type. Lists can be changed and appened (mutable).

mylist = [ "foo", "bar", "baz", "wow" ]

mylist[4] = "new"

print( mylist[4] ) # prints "new"--

Tuples are created with parentheses. They can not be appended nor can elements be replaced (immutable). You would have to create a new tuple with different elements instead.

mytuple = (1, "foo", 3.14159265)

print( mytuple[1] ) # prints "foo"

mytuple[1] = "bar" # TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignmentseq = [ "apple", "banana", "pear", "grape", "plum" ]Slice seq[ start : stop ] copies a sequence from the original sequence, where

start is the index of the first element to copy, and stop is the index of the

element after the last element to copy.

seq[1:3] # ['banana', 'pear']--

Negative indexes count backwards from the end of the list. This works for indexing single elements or slices:

seq[1:-1] # ['banana', 'pear', 'grape']

seq[-3:3] # ['pear']

seq[-1:1] # []--

You may omit either index in the slice to read from the start or to the end of the list:

seq[2:] # ['pear', 'grape', 'plum']

seq[:-3] # ['apple', 'banana']

seq[:] # copy the entire list!A dictionary maps keys to values. It is an unordered collection of key/value pairs.

d = { "foo": 37, "bar": 99, "baz": 42, "woo": 0 }--

Access a key using bracket notation. You can add new keys this way too:

d["foo"] # 37

d["what"] = 45--

Remove a key using del operator:

del d["bar"]--

Use the in operator to check if a key exists:

"foo" in d # True

"noo" in d # FalseA list comprehension is a construct that generates a new list by transforming a list.

The syntax: [ expression for item in list if conditional ]

[x+1 for x in range(10) if x % 2 == 0] # [ 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 ]Define a function using def. Returning a value works similarly to other

languages:

def cube( x ):

return x * x * xVariables in a function are assumed to be local unless marked as global:

glob = 0

def doSomething( x ):

global glob

glob += x

print(glob)--

Global variables are visible within a function but assignment creates a new local which shadows the global.

meaning_of_life = 42

def life(x):

if x == meaning_of_life:

return True

else:

return False

life(39) # false

life(42) # trueFunction arguments can have default values. The arguments are positional, so those with defaults must be specified last in the argument list:

def myfunc( x, y=8, z=5 ):

print(x, y, z)

myfunc( 1, 2 ) # prints (1, 2, 5)--

When you call a function you can specify arguments by name:

myfunc(7, z=9) # prints (7, 8, 9)--

You can use *args and **kwargs to capture arguments without specifying

them in advance:

def my_function(**kwargs):

print str(kwargs)

my_function(a=12, b="abc") # {'a': 12, 'b': 'abc'}You can create an anonymous function in python using lambda:

g = lambda x: x**2 # ** is the exponent operator

g(8) # 64Map transforms a sequence into another sequence. This is equivalent to a list comprehension. Comprehensions are usually considered more 'pythonic':

map( lambda x: x**2, [1,2,3] ) # [1, 4, 9]

[ x**2 for x in [1,2,3] ] # [1, 4, 9]--

Reduce transforms a sequence into a single value. The lambda function takes two arguments which are the first two elements of the list, and in later iterations they are the result of the last call and the next element of the list:

f = lambda a,b: a if (a > b) else b

reduce(f, [47,11,42,102,13]) # 102??? The reduce example is from an online course.

Use the import keyword to import functions from another module:

import random

from math import floor

floor( random.random() * 100 ) # ???--

You create your own modules by creating a new python file (*.py), then you can

import it using the filename minus the extension.

# for file mymodule.py containing function 'myfunction'

import mymodule # mymodule.myfunction()

import mymodule.myfunction # mymodule.myfunction()

from mymodule import myfunction # myfunction()A package is a directory with multiple modules and an __init__.py in it. You

can import the entire package or individual modules or functions.

bash$ ls -la mypackage/

total 0

drwxr-xr-x 4 sherman sherman 136 Jul 29 08:44 .

drwxr-xr-x 9 sherman sherman 306 Jul 29 08:44 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 sherman sherman 0 Jul 29 08:44 __init__.py

-rw-r--r-- 1 sherman sherman 0 Jul 29 08:44 mymodule.py--

# we want to use function 'myfunction'

import mypackage # mypackage.mymodule.myfunction()

import mypackage.mymodule # mypackage.mymodule.myfunction()

from mypackage import mymodule # mymodule.myfunction()

from mypackage.mymodule import myfunction # myfunction()??? python tutorial about modules and packages

Everything in python is an object.

--

Create a class using the class keyword:

class MyClass:

def myfunc(self, x):

print(x)

m = MyClass()

m.myfunc(4) # 4--

Use an __init__ function for a constructor:

class MyClass:

def __init__(self, foo, bar):

self.foo = foo

self.bar = bar

def printme(self):

print(self.foo, self.bar)

m = MyClass(5, 7)

m.printme() # (5, 7)An exercise commonly used in job interviews is Fizz Buzz. We're going to write a Fizz Buzz solution in python using the skills you just learned.

With the numbers 1 through 100, print 'Fizz' if the number is a multiple of 3, or print 'Buzz' if the number is a multiple of 5. If the number is both a multiple of 3 and a multiple of 5, print 'Fizzbuzz'. If the number is not a multiple of either 3 or 5, print the number.

for x in range(100):

n = x+1

if n % 5 == 0 and n % 3 == 0:

print("fizzbuzz")

elif n % 3 == 0:

print("fizz")

elif n % 5 == 0:

print("buzz")

else:

print(n)def prn(w):

print(w)

map( prn,

[ ( "fizzbuzz" if x % 15 == 0 else

( "fizz" if x % 3 == 0 else

( "buzz" if x % 5 == 0 else

x) ) ) for x in

[x+1 for x in range(100)] ])You have now completed the tutorial mission. That means you are now qualified to write python code!

Congratulations on your new skill!