| title | canonical_url | image | description | excerpt | card_src | card_alt | publish_on | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tackling Strongly Correlated Quantum Systems on OSPool |

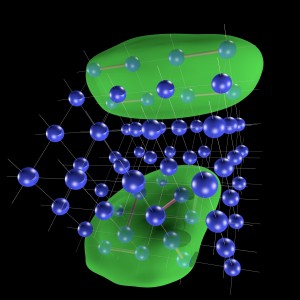

Illustration of a fermion bag configuration. |

|

Duke University Associate Professor of Physics Shailesh Chandrasekharan and his graduate student Venkitesh Ayyar are

using the OSpool to tackle notoriously difficult problems in quantum systems.

|

Duke University Associate Professor of Physics Shailesh Chandrasekharan and his graduate student Venkitesh Ayyar are

using the OSpool to tackle notoriously difficult problems in quantum systems.

|

Illustration of a fermion bag configuration. |

|

Duke University Associate Professor of Physics Shailesh Chandrasekharan and his graduate student Venkitesh Ayyar are using the OSpool to tackle notoriously difficult problems in quantum systems.

These quantum systems are the physical systems of our universe, being investigated at the fundamental level where elemental units carrying energy behave according to the laws of quantum mechanics. In many cases, these units might be referred to as particles or more generally as “quantum degrees of freedom.” The most exciting physics arises when these units are strongly correlated: the behavior of each one depends on the system as a whole; they cannot be taken and studied independently. Such systems arise naturally in many areas of fundamental physics, ranging from condensed matter (many materials fabricated in laboratories contain electrons that are strongly correlated and show exotic properties) to nuclear and particle physics.

The proton, one of the particles inside an atom’s nucleus, is itself a strongly correlated bound state involving many quarks and gluons. Understanding its properties is an important research area in nuclear physics. The origin of mass and energy in the universe could be the result of strong correlations between fundamental quantum degrees.

“Often we can write down the microscopic theory that describes a physical system. For example, we believe we know how quarks and gluons interact with each other to produce a proton. But then to go from there to calculate, for instance, the spin of the proton or its structure is non-trivial,” said Chandrasekharan. “Similarly, in a given material we have a good grasp of how electrons hop from one atom to another. However, from that theory to compute the conductivity of a strongly correlated material is very difficult. The final answer—that helps us understand things better—requires a lot of computation. Typically the computational cost grows exponentially with the number of interacting quantum degrees of freedom.”

According to Chandrasekharan, the main challenge is to take this exponentially hard problem and convert it to something that scales as a polynomial and can be computed on a classical computer. “This step is often impossible for many strongly correlated quantum systems, due to the so-called sign problem which arises due to quantum mechanics,” added Chandrasekharan. “Once the difficult sign problem is solved, we can use Monte Carlo calculations to obtain answers. Computing clusters like the OSG can be used at that stage.”

Chandrasekharan has proposed an idea, called the fermion bag approach, that has solved numerous sign problems that seemed unsolvable in systems containing fermions (electrons and quarks are examples of fermions). In order to understand a new mechanism for the origin of mass in the universe, Ayyar is specifically using the OSG to study an interacting theory of fermions using the fermion bag approach.

Illustration of a fermion bag configuration. Image credit: Shailesh Chandrasekharan“We compute correlation functions on lattices and look at their behavior as the lattice size increases,” Ayyar explained. In the presence of a mass, the correlation functions decay exponentially. “Ideally, we would want to perform computations on very large lattices (>100x100x100). Each calculation involves computing the inverse of large matrices millions of times. The matrix size scales with the lattice size and so the time taken increases very quickly (from days to weeks to months). This is what limits the size of the lattice used in our computation and the precision of the quantities calculated. ”In a recent publication, Ayyar and Chandrasekharan performed computations on lattices of sizes up to 28x28x28, and more recently they have been able to push these to lattices of size 40x40x40.

Since their computation is parallelizable, they can run several calculations at the same time. Ayyar says this makes the OSG perfect for their work. “Instead of running a job for 100 days sequentially,” he noted, “we can run 100 jobs simultaneously for one day to get the same information. This not only helps us speed up our calculation several times, but we also get very high precision.”

Ayyar uses simple scripts to submit a large number of jobs and monitor their progress. One challenge he faced was the check-pointing of jobs. “Some of our jobs run long, say two to six days, and we found these getting terminated before completion due to the queuing system,” Ayyar said. To solve this, he developed what he calls ‘manual check-pointing’ to execute jobs in pieces. “This extends the completed processes and submits them so that long-running processes can be completed. Being able to control the memory and disk-space requirements on the target nodes has proved to be extremely useful.”

Ayyar also noted that many individual research groups cannot afford the luxury of having thousands of computing nodes. “This kind of resource sharing on the OSG has helped computational scientists like us attempt calculations that could not be done before,” he added. “For example, we are now attempting computations on lattices of size 60x60x60. One sweep should only take a few hours on each core.”

Chandrasekharan points out that past technology breakthroughs like the kind that revolutionized processor chip manufacturing have largely been based on basic quantum mechanics learned in the 1940s and 1950s. “We still need to understand the complexity that can be produced when many quantum degrees of freedom interact with each other strongly,” said Chandrasekharan. “The physics we learn could be quite rich.”

He says this next phase of research is already happening in nanoelectronics. “If the computational quantum many-body challenge that we face today is solved, it may help revolutionize the next generation of technology and give us a better understanding of the physics.”

Ayyar and Chandrasekharan recently submitted a paper based on their work using the OSG. Titled Massive fermions without fermion bilinear condensates, it has been published in the journal Physical Review D of the American Physical Society.

– Greg Moore