| title | author | publish_on | type | canonical_url | image | description | excerpt | card_src | card_alt | banner_src | banner_alt | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

LIGO's Search for Gravitational Waves Signals Using HTCondor |

Hannah Cheren |

|

user |

|

Cody Messick, a Postdoc at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) working for the LIGO lab, describes LIGO's use of HTCondor to search for new gravitational wave sources. |

Cody Messick, a Postdoc at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) working for the LIGO lab, describes LIGO's use of HTCondor to search for new gravitational wave sources. |

Image of two black holes from Cody Messick’s presentation slides. |

Image of two black holes from Cody Messick’s presentation slides. |

Cody Messick, a Postdoc at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) working for the LIGO lab, describes LIGO's use of HTCondor to search for new gravitational wave sources.

Image of two black holes. Photo credit: Cody Messick’s presentation slides.High-throughput computing (HTC) is critical to astronomy, from black hole research to radial astronomy and beyond. At the 2022 HTCondor Week, another area of astronomy was put in the spotlight by Cody Messick, a researcher working for the LIGO lab and a Postdoc at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). His work focuses on a gravitational-wave analysis that he’s been running with the help of HTCondor to search for new gravitational wave signals.

Starting with general relativity and why it’s crucial to his work, Messick explains that “it tells us two things; first, space and time are not separate entities but are instead part of a four-dimensional object called space-time. Second, space-time is warped by mass and energy, and it’s these changes to the geometry of space-time that we experience as gravity.”

Messick notes that general relativity is important to his work because it predicts the existence of gravitational waves. These waves are tiny ripples in the curvature of space-time that travel at the speed of light and stretch and compress space. Accelerating non-spherically symmetric masses generate these waves.

Generating ripples in the curvature of space-time large enough to be detectable using modern ground-based gravitational-wave observatories takes an enormous amount of energy; the observations made thus far have come from the mergers of compact binaries, pairs of extraordinarily dense yet relatively small astronomical objects that spiral into each other at speeds approaching the speed of light. Black holes and neutron stars are examples of these so-called compact objects, both of which are or almost are perfectly spherical.

Messick and his team first detected two black holes going two-thirds the speed of light right before they collided. “It’s these fantastic amounts of energy in a collision that moves our detectors by less than the radius of a proton, so we need extremely energetic explosions of collisions to detect these things.”

Messick looks for specific gravitational waveforms during the data analysis. “We don’t know which ones we’re going to look for or see in advance, so we look for about a million different ones.” They then use match filtering to find the probability that the random noise in the detectors would generate something that looks like a gravitational-wave; the first gravitational-wave observation had less than a 1 in 3.5 billion chance of coming from noise and matched theoretical predictions from general relativity extremely well.

Messick's work with external collaborators outside the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA collaboration looks for systems their normal analyses are not sensitive to. Scientists use the parameter kappa to characterize the ability of a nearly spherical object to distort when spinning rapidly or, in simple terms, how squished a sphere will become when spinning quickly.

LIGO searches are insensitive to any signal with a kappa greater than approximately ten. “There could be [signals] hiding in the data that we can’t see because we’re not looking with the right waveforms,” Messick explains. His analysis has been working on this problem.

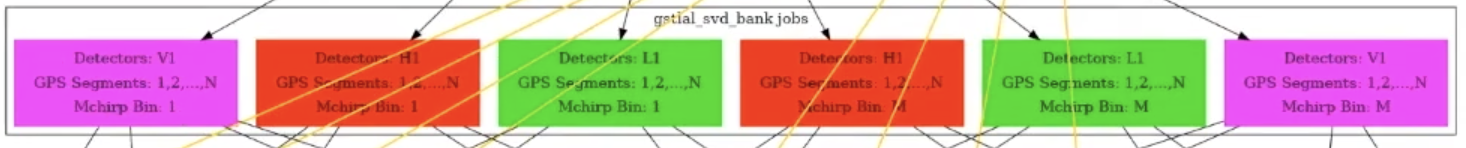

Messick uses HTCondor DAGs to model his workflows, which he modified to make integration with OSG easier. The first job checks the frequency spectrum of the noise. These workflows go into an aggregation of the frequency spectrum, decomposition (labeled by color by type of detector), and finally, the filtering process occurs.

A section of Messick’s DAG workflow.Although Messick’s work is more physics-heavy than computationally driven, he remarks that “HTCondor is extremely useful to us… it can fit the work we’ve been doing very, very naturally.”

...

Watch a video recording of Cody Messick’s talk at HTCondor Week 2022, and browse his slides.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/FcgpmPTXmaA" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>