Greetings everyone who waited for the open course in hands-on data analysis and machine learning to launch!

The first part is about primary data analysis with Pandas.

For now, we plan to have 7 articles that come along with Jupyter notebooks (mlcourse_open repository), competitions and hometasks.

Now comes the list of future articles, course description and the first part itself.

- Primary data analysis with Pandas

- Visual data analysis with Python

- Classification, decision trees and nearest-neighbour method.

- Linear models for classification and regression. Cross-validation and model evaluation

- Ensembles: bagging, random forest. Validation and learning curves

- Unsupervised learning: PCA, clusterization, anomaly detection

- The art of feature engineering and selection. Applications in text mining, image processing and geospatial data

- About the course

- Hometasks in the course

- Demonstration of Pandas main methods

- First try to predict churn rate

- Hometask #1

- Useful links and resources

Many in our OpenDataScience team are involved in state-of-the-art machine learning technologies: DL-frameworks, Bayesian machine learning methods, probabilistic programming and not only. We are currently preparing lectures and practical exercises/workshops on these topics, and in order to prepare audience/students for them, we decided to publish a series of introductory articles on Habr.

We do not aim to develop another comprehensive introductory course on machine learning or data analysis (so it’s not a substitute for the fundamental online and offline programs and books). The purpose of this series of articles is to quickly refresh your knowledge or help you find topics for further study. Approach is similar to that of the authors of the Deep Learning book, which begins with a review of mathematics and the basics of machine learning - short, concise and with many references to sources.

If you plan to take a course, then you should know that when selecting themes and creating materials, we assume that our audience have at least 2nd year knowledge of advanced/higher mathematics and can (write) code in Python. These are not strict selection criteria, but just recommendations - you can enroll in a course without knowing math or Python (or even both!), and simultaneously catch up the following themes:

- Basic math (calculus, linear algebra, optimization, probability theory and statistics) can be reviewed in excellent online courses from MIPT and the Higher School of Economics on Coursera;

- for Python, small interactive tutorial on basic algorithms and data structures from Datacamp of this repository should be enough. For more advanced level see, for example, course from St.Petersburg Computer Science Center;

- As for machine learning, in 95% of cases one will recommend you a classic course from Andrew Ng (Stanford, Coursera). And also some must-reads: "The elements of statistical learning" (Hastie, Tibshirani), "Pattern recognition" (Bishop), "Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective" (Murphy) and "Deep Learning" (Goodfellow, Bengio). The latter book begins with an comprehensive and interesting intro into machine learning and the internal arrangement of its algorithms.

As for now, you’ll only need Anaconda build with Python 3.6 to reproduce the code in the course. Later you’ll need other libraries, but this will be additionally discussed.

Update:

We hope that most of you already know about PyPI, and can install Python 3.6, or even heard of and used venv / virtualenvwrapper, and if you are one of them, use what's more convenient for you (but we do not guarantee full compatibility of course materials with all versions of libraries!).

For all others, install Anaconda: Quick Install Guide. The build includes 100 Python libraries and supports another 720. There is also a light version - Miniconda, but you’ll need to install all the necessary libraries by yourself with it.

You can also use the Docker container that already has all the necessary software. Details are in the README in the repository.

You can join the course any time, but homework deadlines are strict. To participate:

- Fill in the form and indicate your real name and preferably Google email in it (you’ll need google account for homework);

- You can join the OpenDataScience community, the course is discussed in the #mlcourse_open channel.

- Each article goes with homework in the form of Jupyter notebook, where you need to add the code, and, based on this, choose the correct answer in the Google form (that’s what you need a Google account for);

- You can get up to 10 points/credits per homework;

- Each homework is due in 1 week/should be done in 1 week, it’s hard deadline;

- Homework solutions/answers will be posted in the repository right after the deadline;;

- In the end we will publish the rank of participants.

Pandas is a Python library that provides extensive capabilities/means for data analysis. Data scientists work with data that is often stored in table formats, like .csv, .tsv, or .xlsx. Pandas makes it very convenient to load, process and analyze such tabular data using SQL-like queries. And in conjunction with Matplotlib and Seaborn libraries, Pandas provides a wide range of opportunities for visual analysis of tabular data.

The main data structures in Pandas are Series and DataFrame classes. The former is a one-dimensional indexed array of some fixed type data. The latter is a two-dimensional data structure - a table - where each column contains data of the same type. You can represent it as a dictionary of objects of type Series. The structure of DataFrame is great for representing real data: rows correspond to feature description of individual objects, and the columns correspond to the features.

# Make sure that Python 2 and 3 are compatible

# pip install future

from __future__ import (absolute_import, division,

print_function, unicode_literals)

# turn off Anaconda warnings

import warnings

warnings.simplefilter('ignore')

# import Pandas and Numpy

import pandas as pd

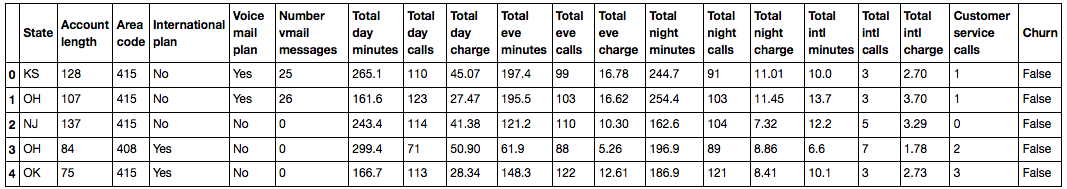

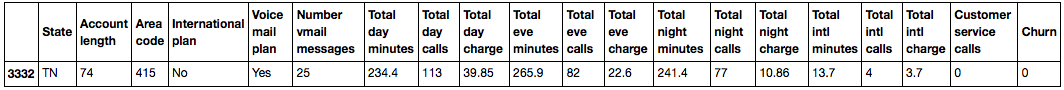

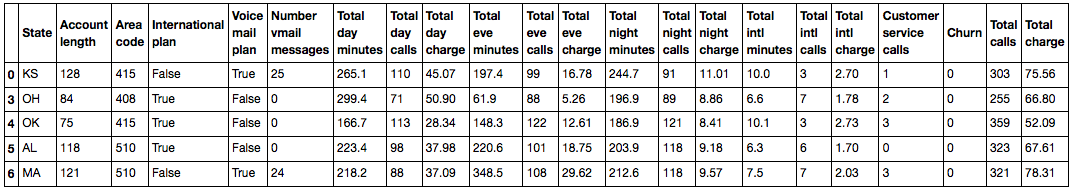

import numpy as npWe’ll show the main methods in action by analyzing dataset on the outflow of customers/churn rate of the telecom operator. Let’s read the data (read_csv method) and look at the first 5 lines using the head() method:

df = pd.read_csv('../../data/telecom_churn.csv')

df.head()

In Jupyter notebooks Pandas dataframes are printed as these pretty tables and `print(df.head())` looks worse. By default, Pandas displays 20 columns and 60 rows, so if your dataframe is bigger use `set_option` function:

pd.set_option('display.max_columns', 100)

pd.set_option('display.max_rows', 100)

Each row is one client - this is the object of research. Columns are features of the object.

| Name | Description | Type | |--- |--: | | | **State** | Letter state code| nominal | | **Account length** | How long the client has been with the company | numerical | | **Area code** | Phone number prefix | numerical | | **International plan** | International Roaming (on/off) | binary | | **Voice mail plan** | Voicemail (on/off) | binary | | **Number vmail messages** | Number of voicemail messages | numerical | | **Total day minutes** | Total duration of calls during day | numerical | | **Total day calls** | Total number of calls during day | numerical | | **Total day charge** | Total charge for services during day | numerical | | **Total eve minutes** | Total duration of calls during evening | numerical | | **Total eve calls** | Total number of calls during evening | numerical | | **Total eve charge** | Total charge for services during evening | numerical | | **Total night minutes** | Total duration of calls during night | numerical | | **Total night calls** | Total number of calls during night | numerical | | **Total night charge** | Total charge for services during night | numerical | | **Total intl minutes** | Total duration of international calls | numerical | | **Total intl calls** | Total number of international calls | numerical | | **Total intl charge** | Total charge for international calls| numerical | | **Customer service calls** | Number of calls to service center | numerical |Target variable is Churn – feature of outflow, it’s binary(1 means the loss of client, i.e. churn). Later we’ll build models that predict this variable based on others, that’s why we called it target.

Let’s have a look at data dimensionality, names of features and their types.

print(df.shape)

(3333, 20)

We can see that table contains 3333 rows and 20 columns. Let’s print out column names:

print(df.columns)

Index(['State', 'Account length', 'Area code', 'International plan',

'Voice mail plan', 'Number vmail messages', 'Total day minutes',

'Total day calls', 'Total day charge', 'Total eve minutes',

'Total eve calls', 'Total eve charge', 'Total night minutes',

'Total night calls', 'Total night charge', 'Total intl minutes',

'Total intl calls', 'Total intl charge', 'Customer service calls',

'Churn'],

dtype='object')

We can use info method to see the general information about data frame:

print(df.info())

bool, int64, float64 and object are types of features. We see that 1 feature is logical (bool), 3 features are of type object and 16 are numeric. We can also use info method to quickly look at the missing values in the data. In our case there are none, each column contains 3333 observations.

We can change column type with astype method. Let’s apply this method to Churn feature and convert it into int64:

df['Churn'] = df['Churn'].astype('int64')

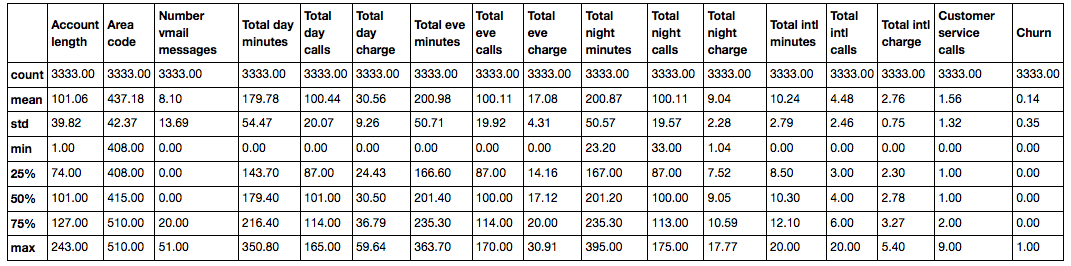

describe method shows the basic statistical characteristics of the data for each numerical feature (int64 and float64 types): number of non-missing values, mean, standard deviation, range, median, 0.25 and 0.75 quartiles.

df.describe()

In order to see statistics on non-numerical features, one needs to explicitly state/indicate types of interest in the include parameter.

df.describe(include=['object', 'bool'])

| State | Area code | International plan | Voice mail plan | Churn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 3333 | 3333 | 3333 | 3333 | 3333 |

| unique | 51 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| top | WV | 415 | No | No | False |

| freq | 106 | 1655 | 3010 | 2411 | 2850 |

df['Churn'].value_counts()

0 2850

1 483

Name: Churn, dtype: int64

2850 users of 3333 are loyal, their Churn value is 0.

Let’s have a look at users distribution over/according to the Area code variable. We’ll set parameter normalize=True to see relative frequencies, not absolute.

df['Area code'].value_counts(normalize=True)

415 0.496550

510 0.252025

408 0.251425

Name: Area code, dtype: float64

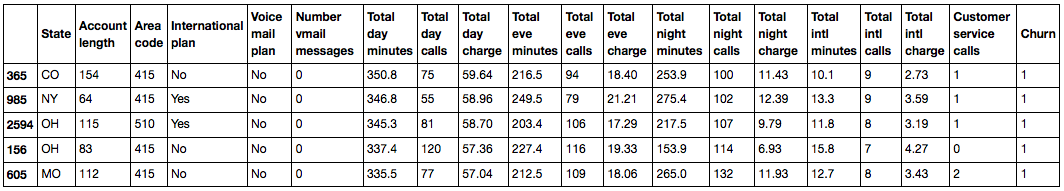

DataFrame can be sorted by the value of one of the variables. In our case, for example, it can be sorted by Total day charge (ascending=False for sorting in descending order):

df.sort_values(by='Total day charge',

ascending=False).head()

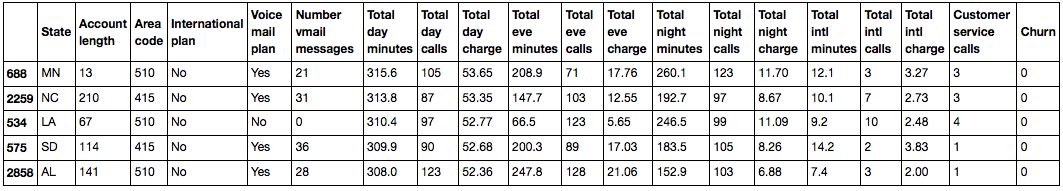

We can also sort by group of columns:

df.sort_values(by=['Churn', 'Total day charge'],

ascending=[True, False]).head()

спасибо за замечание про устаревший sort @makkos

DataFrame can be indexed in different ways. That said, let’s consider various ways of indexing and retrieving the data we need from the dataframe using simple questions.

To retrieve a single column, you can use a DataFrame ['Name'] construct. Let's use this to answer the question: what is the proportion of disloyal users in our dataframe?

df['Churn'].mean()

0.14491449144914492

14.5% is quite bad for a company, with such churn rate it is possible to go bankrupt.

DataFrame logical indexing by one column is also very convenient. It looks like this: df[P(df['Name'])], where P is some logical condition that is checked for each element of the Name column. The result of such indexing is the DataFrame consisting only of rows that satisfy the P condition on the Name column.

Let’s use it to answer the question: What are average values of numerical variables for disloyal users?

df[df['Churn'] == 1].mean()

Account length 102.664596

Number vmail messages 5.115942

Total day minutes 206.914079

Total day calls 101.335404

Total day charge 35.175921

Total eve minutes 212.410145

Total eve calls 100.561077

Total eve charge 18.054969

Total night minutes 205.231677

Total night calls 100.399586

Total night charge 9.235528

Total intl minutes 10.700000

Total intl calls 4.163561

Total intl charge 2.889545

Customer service calls 2.229814

Churn 1.000000

dtype: float64

Let’s use the combination of two above methods to answer the following question: How much time do disloyal users spend on phone in average during a day?

df[df['Churn'] == 1]['Total day minutes'].mean()

206.91407867494823

What is the maximum length of international calls among loyal users (Churn == 0) who do not use the international roaming service ('International plan' == 'No')?

df[(df['Churn'] == 0) & (df['International plan'] == 'No')]['Total intl minutes'].max()

18.899999999999999

DataFrames can be indexed both by column or row name, or by the serial number. loc method is used for indexing by name, iloc - for indexing by the number.

In the first case we say "give us the values of the first five rows in the columns from State to Area code", and in the second - "give us the values of the first five rows in the first three columns".

df.loc[0:5, 'State':'Area code']

| State | Account length | Area code | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | KS | 128 | 415 |

| 1 | OH | 107 | 415 |

| 2 | NJ | 137 | 415 |

| 3 | OH | 84 | 408 |

| 4 | OK | 75 | 415 |

| 5 | AL | 118 | 510 |

df.iloc[0:5, 0:3]

| State | Account length | Area code | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | KS | 128 | 415 |

| 1 | OH | 107 | 415 |

| 2 | NJ | 137 | 415 |

| 3 | OH | 84 | 408 |

| 4 | OK | 75 | 415 |

df[-1:]

To apply functions to each column, use apply:

df.apply(np.max)

State WY

Account length 243

Area code 510

International plan Yes

Voice mail plan Yes

Number vmail messages 51

Total day minutes 350.8

Total day calls 165

Total day charge 59.64

Total eve minutes 363.7

Total eve calls 170

Total eve charge 30.91

Total night minutes 395

Total night calls 175

Total night charge 17.77

Total intl minutes 20

Total intl calls 20

Total intl charge 5.4

Customer service calls 9

Churn True

dtype: object

apply method can also be used to apply a function to each line. To do this, specify axis=1.

To apply functions to each cell of the column, use map.

For example, map method can be used to replace values in a column by passing it a dictionary of the form {old_value: new_value} as an argument:

d = {'No' : False, 'Yes' : True}

df['International plan'] = df['International plan'].map(d)

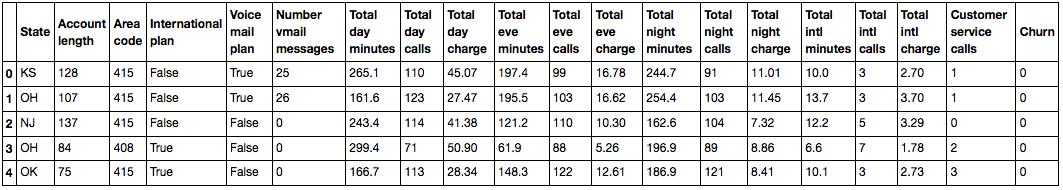

df.head()

Same thing can be done with replace method:

df = df.replace({'Voice mail plan': d})

df.head()

In general, grouping of data in Pandas goes as follows:

df.groupby(by=grouping_columns)[columns_to_show].function()

- First,

groupbymethod is applied to DataFrame; it divides data according to thegrouping_columns- one or several variables. - Then, columns of interest are selected (

columns_to_show). - Finally, one or several functions are applied to the obtained groups.

Here’s how grouping of data according to the value of Churn variable and displaying statistics on three columns in each group is implemented:

columns_to_show = ['Total day minutes', 'Total eve minutes', 'Total night minutes']

df.groupby(['Churn'])[columns_to_show].describe(percentiles=[])

| Total day minutes | Total eve minutes | Total night minutes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Churn | ||||

| 0 | count | 2850.000000 | 2850.000000 | 2850.000000 |

| mean | 175.175754 | 199.043298 | 200.133193 | |

| std | 50.181655 | 50.292175 | 51.105032 | |

| min | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 23.200000 | |

| 50% | 177.200000 | 199.600000 | 200.250000 | |

| max | 315.600000 | 361.800000 | 395.000000 | |

| 1 | count | 483.000000 | 483.000000 | 483.000000 |

| mean | 206.914079 | 212.410145 | 205.231677 | |

| std | 68.997792 | 51.728910 | 47.132825 | |

| min | 0.000000 | 70.900000 | 47.400000 | |

| 50% | 217.600000 | 211.300000 | 204.800000 | |

| max | 350.800000 | 363.700000 | 354.900000 |

columns_to_show = ['Total day minutes', 'Total eve minutes', 'Total night minutes']

df.groupby(['Churn'])[columns_to_show].agg([np.mean, np.std, np.min, np.max])

| Total day minutes | Total eve minutes | Total night minutes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | std | amin | amax | mean | std | amin | amax | mean | std | amin | amax | |

| Churn | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 175.175754 | 50.181655 | 0.0 | 315.6 | 199.043298 | 50.292175 | 0.0 | 361.8 | 200.133193 | 51.105032 | 23.2 | 395.0 |

| 1 | 206.914079 | 68.997792 | 0.0 | 350.8 | 212.410145 | 51.728910 | 70.9 | 363.7 | 205.231677 | 47.132825 | 47.4 | 354.9 |

Suppose we want to see how the observations in our sample are distributed in the context of two variables - Churn and International plan. To do so, we can build a contingency table using crosstab method:

pd.crosstab(df['Churn'], df['International plan'])

| International plan | No | Yes |

|---|---|---|

| Churn | ||

| 0 | 2664 | 186 |

| 1 | 346 | 137 |

pd.crosstab(df['Churn'], df['Voice mail plan'], normalize=True)

| Voice mail plan | No | Yes |

|---|---|---|

| Churn | ||

| 0 | 0.602460 | 0.252625 |

| 1 | 0.120912 | 0.024002 |

Advanced Excel users will probably remember about such a feature as pivot tables. In Pandas, pivot_table method is responsible for pivot tables, it takes the following parameters:

*values - list of variables for which one needs to calculate statistics;

*index – list of variables according to which to group data,

*aggfunc — what statistics we need to calculate for groups - sum, mean, maximum, minimum or something else.

Let’s take a look at average number of day, evening and night calls for different Area codes:

df.pivot_table(['Total day calls', 'Total eve calls', 'Total night calls'], ['Area code'], aggfunc='mean').head(10)

| Total day calls | Total eve calls | Total night calls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Area code | |||

| 408 | 100.496420 | 99.788783 | 99.039379 |

| 415 | 100.576435 | 100.503927 | 100.398187 |

| 510 | 100.097619 | 99.671429 | 100.601190 |

Like many other things in Pandas, adding columns to the DataFrame is feasible in several ways.

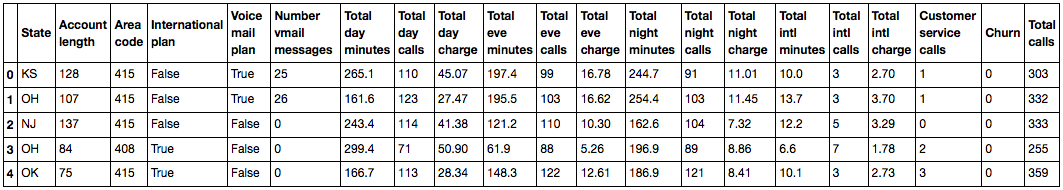

For example, we want to calculate the total number of calls for all users. Let’s create total_calls object of type Series and paste it into the data frame:

total_calls = df['Total day calls'] + df['Total eve calls'] + df['Total night calls'] + df['Total intl calls']

df.insert(loc=len(df.columns), column='Total calls', value=total_calls)

# loc is the number of column after which to insert the Series object

# we set it to len(df.columns) to paste it in the very end

df.head()

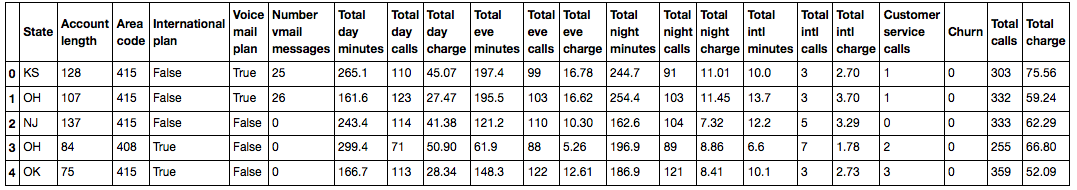

It is possible to add a column from existing ones in an easier way, without creating intermediate Series:

df['Total charge'] = df['Total day charge'] + df['Total eve charge'] + df['Total night charge'] + df['Total intl charge']

df.head()

To delete columns or rows, use drop method, passing it the required indexes and the required value of the axis parameter (1 if you delete the columns, and nothing or 0 if you delete the rows) as the argument:

df = df.drop(['Total charge', 'Total calls'], axis=1) # get rid of the just created columns

df.drop([1, 2]).head() # and here’s how you can delete rows

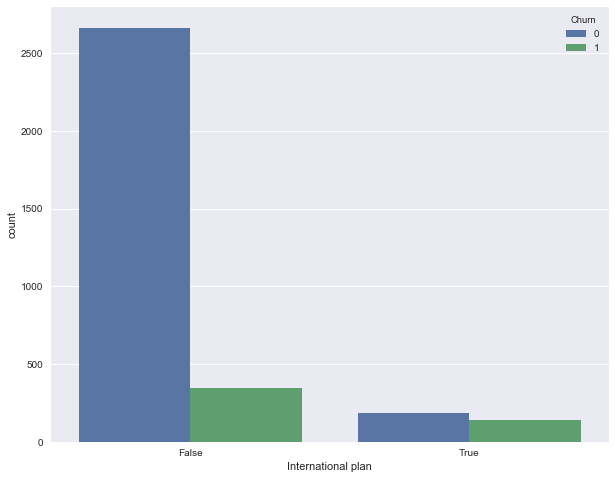

Let's see how churn rate is connected with the International plan variable. We’ll do this using a crosstab contingency table and Seaborn illustration/visualisation (we’ll cover the material on how to build such pictures and make sense of them in the next article).

pd.crosstab(df['Churn'], df['International plan'], margins=True)| International plan | False | True | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Churn | |||

| 0 | 2664 | 186 | 2850 |

| 1 | 346 | 137 | 483 |

| All | 3010 | 323 | 3333 |

We see that when roaming is switched on, churn rate is much higher - that’s an interesting observation! Perhaps large and poorly controlled spending/expenses in roaming is very conflict-prone/triggers conflicts and leads to discontent/dissatisfaction of the telecom operator's customers and, accordingly, to their churn.

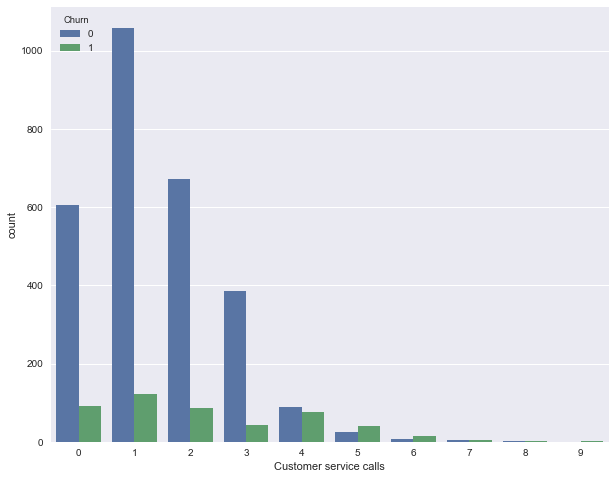

Next, let’s look at another important feature - "Number of calls to the service center" (Customer service calls). Let’s also make a summary table and a picture.

pd.crosstab(df['Churn'], df['Customer service calls'], margins=True)| Customer service calls | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Churn | |||||||||||

| 0 | 605 | 1059 | 672 | 385 | 90 | 26 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2850 |

| 1 | 92 | 122 | 87 | 44 | 76 | 40 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 483 |

| All | 697 | 1181 | 759 | 429 | 166 | 66 | 22 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 3333 |

Perhaps, it is not so obvious from the summary table (or it's boring to creep along the lines with numbers), but the picture eloquently testifies that the churn rate strongly increases from 4 calls to the service center.

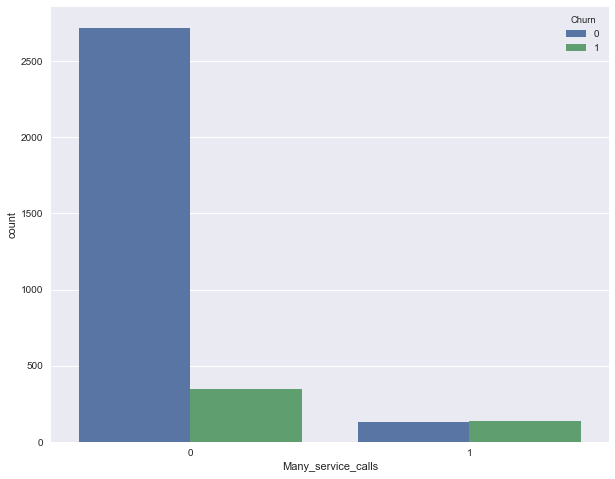

Let’s now add a binary attribute to our DataFrame - the result of the comparison Customer service calls > 3. And once again, let's see how it relates to the churn.

df['Many_service_calls'] = (df['Customer service calls'] > 3).astype('int')

pd.crosstab(df['Many_service_calls'], df['Churn'], margins=True)| Churn | 0 | 1 | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Many_service_calls | |||

| 0 | 2721 | 345 | 3066 |

| 1 | 129 | 138 | 267 |

| All | 2850 | 483 | 3333 |

Let’s merge conditions from above and construct a summary table for this union and churn.

pd.crosstab(df['Many_service_calls'] & df['International plan'] , df['Churn'])| Churn | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| row_0 | ||

| False | 2841 | 464 |

| True | 9 | 19 |

In general, before the advent of machine learning, the data analysis process looked something like this. Let's recap:

- The share of loyal clients in the sample is 85.5%. The most naive model that always predicts a "loyal customer" on such data will guess right in about 85.5% of cases. That is, the proportion of correct answers (accuracy) of subsequent models should be not less, and better significantly higher than this number;

- With the help of a simple forecast that can be expressed by the following formula: "International plan = False & Customer Service calls <4 => Churn = 0, else Churn = 1", we can expect a guessing rate of 85.8%, which is just above 85.5%. Subsequently, we'll talk about decision trees and figure out how to find such rules automatically based only on the input data;

- We got these two baselines without any machine learning, and they’ll serve as the starting point for our subsequent models. If it turns out that with enormous efforts we enlarge the share of correct answers by, say, 0.5%, then perhaps we are doing something wrong, and it suffices to confine ourselves to a simple model with two conditions;

- Before training complex models it is recommended to twist the data a little and check simple assumptions. Moreover, in business applications of machine learning, they usually start with simple solutions, and then experiment with their complications.

The first homework assignment is devoted to the analysis of the Adult data set of the UCI repository and is presented in this Jupyter notebook. This dataset contains demographic information of the residents of the United States.

We suggest that you complete this task and then answer 10 questions. Here’s the link to the form for answers (you can also find it in the notebook). Answers in the form can be changed after sending, but not after deadline (well, technically it is possible even after deadline, but it will not be credited).

Hard deadline: March 6 23:59

- First of all, of course, the official documentation of Pandas. In particular, we recommend a short introduction of 10 minutes to pandas, PDF-шпаргалка по библиотеке,

- PDF-шпаргалка по библиотеке,

- Отличная презентация Александра Дьяконова «Знакомство с Pandas»,

- На гитхабе есть подборка упражнений по Pandas и еще один полезный репозиторий (на английском языке),

- scipy-lectures.org — учебник по работе с pandas, numpy, matplotlib и scikit-learn.

The article is written in association with @yorko (Yuri Kashitski) and with ODS community support