Unknown subterranean areas can be dangerous for humans to discover and survey. To minimize the dangers of an underground exploration project one can employ state of the art robotics. A central problem in underground exploration is the fact that navigating by satnav is, at best, unreliable. Simultaneous localization and mapping[1] (SLAM) aims to solve this problem by localizing an autonomous robot while building a map that is consistent with the environment. By deploying multiple robots, a map can be constructed in a more time-efficient manner. Multiple robots can explore an area more efficiently by sharing their knowledge. This paper describes a SLAM based underground navigation, map merging using Hough peak matching[2], a local navigation controller for ensuring optimal wall distance and integration of a camera in a simulated environment. Further improvements are also expanded upon. The team assigned to this project consisted of seven students from the Luleå University of Technology. Each student had a background in computer science or electrical engineering and control theory. The project was carried out over a span of 20 weeks. Weekly progress updates were presented for the students partaking in the course and group meetings were scheduled twice per week.

The robotic hardware used for the project was a Turtlebot 3 Burger (TB3B), provided by the robotics department within Luleå University of Technology for its size and the components. The TB3B layout consisted of 4 stacked layers, each with their own set of components. The first (base) layer held the two DYNAMIXEL XL430-W250 actuators and a slot for the lithium polymer battery. By having two actuators the TB3B would be able to traverse at a higher speed with less stress and gain more freedom during turns. The second layer held the OpenCR1.0 board that worked as the middleman between the actuators, battery and the Raspberry Pi. Its main purpose was to control the actuators for the TB3B, but it also helps the power switch and distribution for the system. The third layer held the brain of the system, the Raspberry Pi 3 Model B. The Raspberry Pi was installed with a Ubuntu MATE 18.04 operating system, which handled the backend software for sending the robots gathered data to the central station, and the navigation system, which made sure that the robot did explore an already explored area. On the final top layer were the eyes of the robot, a 360° Laser Distance Sensor LDS-01 LiDAR. The LiDAR constantly scanned and gathered data about its surroundings which were sent down to the Raspberry Pi for processing.

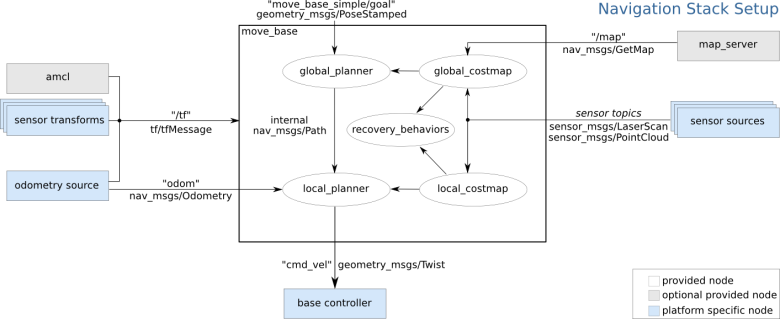

The Robot Operating System[3] (ROS) is a set of software packages and tools that help out with the creation of robotic applications. ROS provides libraries that support a vast amount of functionality one could desire from a robot e.g. navigation and SLAM. These two features were used extensively within the project. ROS also provides tools for simulation and visualization. These tools were used in debugging the application and test if the desired behaviour had been reached before the application was deployed into a real-world scenario for further benchmarking. A ROS application is made up of several nodes in a network called a ROS graph, where each node is a process that performs computation. Nodes are meant to operate on a very granular scale and a ROS application will, therefore, comprise of many nodes. In the case with the TB3B, there is, for example, one node controlling the LiDAR, one controlling the motors to the wheels and one node performing localization. Nodes communicate with each other by publishing messages to topics which are then subscribed to by other nodes. A message can contain a range of different data types. Standard primitive types are supported as are arrays of them. Messages also come in the form of service calls where a node sends a request message to a node to receive a reply in the form of a response message. Topics are named buses which nodes send messages over. Topics generate messages even if there is no subscriber. Nodes do not know who they are communicating with, it works on the same principle as FM radio where the interested will tune themselves to the continuous broadcast to find the information they are interested in. This model is however not appropriate for request and reply interactions between nodes. A concept known as a service is used to solve this problem. These can often be treated as if they were remote procedure calls.

The Cartographer system is derived from Google’s repository in GitHub[4] where the system is an open-source project. This system’s main focus is to be a solution to the simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) problem that is about how one can do both localization and mapping at the same time.

Cartographer is an algorithm used to get a representation of the local environment given useful sensor data. For localization and mapping of the local environment, SLAM solving is the main reason to use Cartographer. It contains two SLAMs, a local SLAM, and a global SLAM. The local SLAM's function is to generate approved submaps with correct scans (range data) and the global SLAM combines all submaps and creates a global map. The Global map can then be used to visually represent the environment.

The usefulness of this system is in the quality of representing the environment, high-resolution maps can be easily created with this system. Cartographer itself creates a compressed file (pbstream) as an output. The file only contains what Cartographer claims to be useful sensor data. Then when recombined with the full sensor data file (bag) creating a high-resolution map. Although it is in the interest of the project to combine multiple maps from multiple robots into one map, there was no clear way to do that with the system. Instead, the output file in interest became a portable grey map (PGM file). For Cartographer to work with the rest of the parts, necessary tuning on the system’s parameters had to be done to work with the turtlebot3.

There are several steps to do when it comes to detecting lines in an image. For starters, only the necessary data such as the edges on the map representing the walls was wanted. The research paper used the Canny Edge Detection[5] approach to detect the edges in an image. Canny Edge Detection is a multi-step algorithm where the goal is to create a binary representation of the image where ones are walls and zeros are everything else. First, it’s using gaussian blur as filtering out noises before running what is known as Sobel edge detection. This ensures that much of the unwanted edges are removed. From here threshold and hysteresis are applied to result in the binary image with only the edges left.

When the newly created image with Canny Edge is done, Hough Transform was the next step. Hough Transform takes advantage of mapping each pixel coordinates to a corresponding line in Hough Space. Since each pixel has a fixed known X and Y coordinate value which can be transformed into a polar coordinate with ⍴ and θ as the axis.

⍴=Xcos(θ)+Ysin(θ)

Thus each pixel in the Image Space represents a sinusoid line in Hough Space. When multiple pixels gets a representation in Hough Space there will be a bunch of intersection points with same ⍴ and θ in Hough Space where the lines meet. These intersection points in Hough Space mapped back to the Image Space gives the most common lines in the image. By here the walls have been detected given the ⍴ and θ values to Image Space.

Y=-(cos(θ)/sin(θ))X+(⍴/sin(θ))

The project has two major components in its design, the Turtlebot and the Central station. As illustrated in figure 1 both the Turtlebot and the Central station holds its internal components.

| System design |

|---|

|

| Figure 1 |

Figure 1 also shows that the Turtlebot has sensor data that feeds into the Raspberry Pi. The Raspberry Pi has the cartographer algorithm running on it. Cartographer forwards its generated map into the global costmap. The map is also saved from cartographer and transferred through SSH SCP to the Central station.

The Central station takes care of the merging process. Once complete it will send the merged map back to the Turtlebot through SSH SCP, where the global costmap receives it.

The map merging script starts by extending the length and height of the images to the initial hypotenuse, that way no matter how it is rotated it will still fit on the canvas. Then it runs the canny edge detection on the two images that are supposed to be merged. This is done to remove any area that is between the edges of the walls as it will clutter the hough images that are created. It will then create a hough image of each of the edge detected maps.

Once the hough images are created it will run through each one of them and create an array of the maximum intensity on each angle where in our case the hough image has a resolution of 1280x720 pixels which means that each angle interval is 0.14°. This is the same as running the max function over each column.

This resulting array is then passed into a function that runs a periodic cross-correlation between the two given arrays. From the cross-correlation, the different rotation hypotheses are given by finding the local peaks in the array given from the cross-correlation. These peaks will be given as a pixel location on the x-axis which is then converted to a degree instead. This is done using the knowledge that the hough image goes from -90° to 90° as well as that the hough image is 1280 pixels wide. The given equation is then (x/1280)180-90.

The next step in the process of finding the correct hypothesis, this is done using the Multiple Hypothesis Handling (Algorithm 1) which is given in the research paper Map Merging Using Hough Peak Matching. The result is a hypothetical angle which is compared to the rotational hypotheses, the one closest to the hypothetical angle is chosen as the “correct” hypothesis. The original non-extended image is then rotated and then once again extended to the same size as before. Then the rotated map is run through the edge detection and hough transformation again as well as max function described above, lastly before moving on to the next step all the local peaks are found.

The next step is the translation, this is also done according to the research paper mentioned above. The paper states that to find the translation matrix TO the equation

(which can also be written as B = ATO,) must be solved, this is done by calculating the matrices A and B. To find the 𝞺 and 𝞱, Algorithm 2 from the research paper is used which is similar to Algorithm 1, the difference is that 𝞺 is also considered when matching the peaks and instead of looking over the whole all 𝞱 when comparing it only compares within a short range of the reference point that it compares to. When all matching peaks have been found it calculates A and B by finding the respective 𝞺 and 𝞱 and puts it in the equation above where 𝞺1’ is the 𝞺 from the map that is to be moved. In TO the number in the first row is the offset for the x-coordinate and the lower row is for the y-coordinate. Once TO is calculated the new coordinates for the rotated map are calculated by offsetting the centre of the rotated image from the centre of the first image with the values from TO. This is where the maps are then merged and saved

The software Rviz[6] is a 3D visualizer created for the ROS framework. It was used to visualize published information from the robot and also used in a later stage to issue commands to the robot for navigation purposes. The software was chosen because of its tight integration with the ROS framework and ease of use. The TB3B and the world it was navigating was simulated using the software Gazebo [7]. Gazebo is unlike Rviz, not developed solely for use within ROS. A set of interfaces is therefore provided with ROS for ROS-like communication with Gazebo using messages, services and still allowing for dynamic reconfigure. This made Gazebo the obvious choice for the simulation of the TB3B and its interaction with the simulated world.

Rviz makes use of a file format called Universal Robotic Description Format (URDF). A URDF file describing the TB3B was used to describe the robot and its capabilities to Rviz. A camera was to be added to the real world robot and therefore a camera had to be added to the URDF describing the simulated robot. The camera was however never added to the real world robot. URDF files are written in XML by using the macro language xacro. This made the URDF files easier to maintain and to read. The software Gazebo makes use of a file format called Simulation Description Format (SDF). SDF was developed to solve the shortcomings of URDF. SDF specifies additional properties such as friction, lights, height maps etc. Another improvement that SDF has is that it does not break proper formatting with heavy use of XML attributes and is thus more flexible in its implementation. It is possible to convert URDF into SDF. This allows a URDF file be used with Gazebo after it has been converted to SDF. This process was carried out automatically.

ROS makes use of topics to send messages from a publisher to a subscriber. Gazebo published simulation messages which were computed within the ROS framework and then published to Rviz for visualization. The first tests were carried out by following the tutorials available for the TB3B. The goal was first to make sure that the camera had been implemented correctly and thus Rviz was made to only visualize the camera feed. The script that described what to visualize was extended significantly as the project went on. By using Rviz, a 2D goal point was successfully published to the TB3B and all relevant topics were received correctly. By following the earlier mentioned tutorials for the TB3B it became possible to navigate on a known map in a simulated world with the modified TB3B model.

The LIDAR was used to gather all the data used to map the environment. The raw data was processed by the Cartographer algorithm within the Raspberry Pi, to generate a temporary map file and an accessory data file to the map. These two files were then sent onward to the central station.

| The Cartographer ROS node | The Navigation Stack |

|---|---|

|

|

| Figure 2 | Figure 3 |

The navigation system comprised SLAM provided by the Cartographer online node and a library of navigation packages known as the ROS Navigation Stack[8]. The submap list of Cartographer was sent as map data into the stack and then globally and locally planned upon. The local planner that was used in the first tests was the default Dynamic Window Approach Planner (DWAP) but later in the project, a new local planner was innovated and implemented into the ROS Navigation Stack. The global plan was generated by the default global planner known simply as global_planner.

The robot needs to be able to navigate unknown environments, a robust and reliable control system is needed to achieve this.

|

|---|

| Figure 4 |

In the illustration above the structure of the control system and its supporting components.

The purpose of the global navigator is to find a path the robot should follow to reach its goal. The goal points are set manually and when the robot reaches it, a new one will be chosen by the operator. It will use information from the global map, a map of the combined scans from all robots. This was implemented using the already existing ROS package move_base that calculates a global path for the robot using Dynamic Window Approach Planner algorithm.

The Global Navigator uses maps generated from cartographer, which is a slow process, combined with A-star not being a particular fast algorithm. This makes the Global Navigator a rather slow. This is solved with a Local Navigator.

The Local Navigator's purpose is to avoid obstacles and keeping an optimal distance to walls, this to give optimal scanning quality. It will follow the direction of the path given by the Global Navigator.

A custom ROS node was implemented to solve this. The node operates by giving all point seen by the lidar a virtual force, see equation above, which when combined creates an heat map. The node then solves the gradient of the heat map in the position of the robot, as in the equation below. The value of lp is the distance to the point, and the values c and n is tuning-parameters, which was tuned manually. The resulting vector will then point in a direction away from all obstacles.

Finely the gradient vector is combined with a directional vector which is the direction that the path is currently pointing. The resulting vector, if followed will take the robot toward its goal while avoiding obstacles and keep an equal distance to the walls on both sides.

The Path Follower is a controller that control the speed of the robots actuators.

It follows the direction given by the Local Navigator such that the point P in the figure below, is always facing the correct direction. The control system will achieve this by changing speed relation between the wheels on the robot, making it turn.

| Figure 5 |

To simplify the system, some assumptions were made. Because the robot is equipped with strong motors and wheels with a good grip, the assumption was made that the robot will not lose its grip. The system is also assumed to have a near-perfect step response. With these assumptions the system will be static, only changing when moved by actuator.

| Figure 6 |

By making the final assumption that the target point T, in the figure above, is stationary then a new variable, d, can be introduced as in equation below.

By making the final assumption that the target point T, in the figure above, is stationary than a new variable, d, can be introduced as in equation below.

Because the system is of first order, by using the assumptions from the previous section, the optimal controller will be a P controller, as seen in equation below.

The variable p, in the equation above, was chosen in simulations for optimal performance.

Central station's purpose is to control and communicate with the TB3Bs. From the central station, all packages are run through the scripts which contains the essential ROS commands. Also, the ROS master node is started through ROS command roscore at central station. Its role is to look over the other active nodes and help them locate each other. ROS Master also comes with a parameter server which will store and retrieve parameters from nodes. These parameters are XMLRPC data types which are XML equivalents of common data types.

There are several options when it comes to data transfer between each robot and the central system. In this project, multiple solutions have been considered. Continuous data streaming would be the ideal solution since it would allow the system to update the global map from all sources continuously during runtime. This is however hard to implement in an unexplored cave system were connectivity is likely to be limited. This limitation is mainly caused by the nature of this project. It goes without saying that in an unexplored environment there will not be any wireless access points for the robot to connect to during runtime. Wireless connectivity will also be blocked by the thick cave walls. Satellite connection is not viable either due to the robot being located underground. A wired connection is a somewhat reasonable solution although it presents other, more physical, limitations. For example, it would limit the range each robot could go before being stopped by the wire. It could also cause problems if the wire gets stuck on something in the terrain or if the robot gets tangled in the wire.

Another solution is to allow each robot to venture out on its own and generate a local map that is stored locally on the robot. It would then return to its starting point after a certain condition has been met, be that in distance or time travelled. Once back at the starting point it could then transfer the local map to the central station where it would be merged into the global map. The updated global map would then be passed back to the robot and it could go back to exploring with the new data.

Naturally, this introduces some other limitations. For example, if one robot returns and updates the global map, the other robots won’t be aware of this new data until each has gone back to update. This could result in multiple robots exploring the same area. It also causes robots to go through the same path twice since it has to return home, which in turn reduces efficiency.

Ideally, the streaming solution would be the one used. If this is not attainable however a different path needs to be taken. Each of these solutions comes with certain compromises. They are all viable in different situations and it would, therefore, have to be decided on a case by case basis which solution is to be implemented. Consider instead an unexplored building on the ground level. In such a scenario satellite connectivity could be implemented to transfer data. Consider a cave that has been previously explored but not entirely mapped out. In such a scenario there could exist access points for robots to connect to. In the end, one should commit to only employ a single solution for all tasks but instead consider the alternatives.

Data streaming capabilities is a straightforward implementation due to the underlying ROS framework. ROS supports something they call ‘topics’ which is simply a way for nodes to publish data and other nodes to subscribe to that data stream. In this case, each robot would be a separate node to which the master node subscribes to. The master node is the central station. As for topics, they have anonymous publish/subscribe semantics, which decouples the production of information from its consumption. In general, nodes are not aware of who they are communicating with. Instead, nodes that are interested in data subscribe to the relevant topic; nodes that generate data publish to the relevant topic. There can be multiple publishers and subscribers to a topic. This would also allow each robot to subscribe to all other data feeds which would ensure that all robots are constantly aware of what the others are doing in the network.

ROS topics currently support both UDP and TCP message transport. Using the already implemented TCP ensures minimal package loss. Since data isn’t stored indefinitely on each unit it becomes difficult to validate that all robots possess the same, and correct data. Package loss must be minimized. Otherwise, the quality of the map could quickly deteriorate and present holes of missing data points on the global map.

The robot is running the Linux operating system ubuntu MATE. The central station is also running a version of ubuntu. This allows access to common bash commands like SSH which lets the user remotely connect to the robot. It also allows for easy file transfer via shell SCP commands. When the robot has a stable connection it can then transfer data to the central station. Which will, in turn, send back the updated global map. There is a shell script that will automate this process, although that is not entirely implemented. The downside of this approach is that both parties require bash terminal functionality. It also doesn’t support active data streaming, instead, it only transfers complete files. The shell script can be adjusted to send updates very frequently but even then it does not equal a continuous data stream. The positives are down to how robust this SCP command is. It will ensure that data is transferred in its entirety. It features extensive error detection in which an error will be properly raised and can then be handled in software. It also manages all the networking going on behind the scenes by opening and closing ssh connections properly and since it is run in a shell instance it also handles multiprocessing.

The TB3B and the central station both connect to a separate wifi network. Turtlenet is a wireless network setup to allow communication between the central station and robot. This network is propagated by a wireless router supplied by the control group at LTU. The wifi network already available at LTU could not be used due to limited access available to students, data could not be transferred from one point to another. In turn, this blocks the usage of wifi access points located in the testing area. When the robot is running it will, therefore, be limited in the travel range.

The two maps received from the map saver:

|

|

|---|---|

| Figure 7 | Figure 8 |

The two maps run through the extender:

|

|

|---|---|

| Figure 9 | Figure 10 |

The two maps after the canny edge detection has been run:

|

|

|---|---|

| Figure 11 | Figure 12 |

The resulting hough images:

|

|

|---|---|

| Figure 13 | Figure 14 |

The maximum intensities over the theta of the hough images:

|

|---|

| Figure 15 |

|

|---|

| Figure 16 |

The result of the periodic cross-correlation (and of note is that the minimum value on the graph is 41040527 and the maximum value is 42441750).

|

|---|

| Figure 17 |

The following two images are the given rotational hypotheses:

|

|

|---|---|

| Figure 18 | Figure 19 |

The following image is the chosen one by the algorithm after it has been run through the preprocessing until after the Canny edge detection:

|

|---|

| Figure 20 |

The next image is the hough space and the result from running the max function over the columns:

|

|

|---|---|

| Figure 21 | Figure 22 |

The calculated translation matrix:

This is the combined maps after the translation is applied:

|

|---|

| Figure 23 |

| The camera added to TB3B (Grey cube). | The transform frame tree. Note that the odometry is provided by Gazebo. |

|---|---|

-2019-10-07T09_31_48.707295.jpg) |

|

| Figure 24 | Figure 25 |

The camera was successfully added to the already provided TB3B URDF and functioned as a real-world camera would have. No mesh data was created to simulate the visual appearance of the camera. The simulated TB3B and the added camera is shown in figure 24. The camera is displayed as a grey cube. The output from the camera mounted to the TB3B model in the simulated environment can be seen in figure 30. The camera was not integrated into the real world system as it was discovered that it would not be used by the software in any meaningful way. Figure 25 shows the TF tree that was used during the simulations. The odometry frame that was published from Gazebo was used instead of the odometry frame that is provided by Cartographer to remove transform re-parenting errors. Multiple TB3B with the developed software solution were simulated. These simulations were mostly unsuccessful as there were a multitude of problems with transforms being incorrectly interpreted by Gazebo, e.g. multiple TB3B sharing the same virtual space in the simulated environment.

| The Turtle World | The House World |

|---|---|

|

|

| Figure 26 | Figure 27 |

The two worlds that were used were the house world and the turtle world. they are displayed orthographically in figure 26 and 27. The turtle world was chosen for its simplicity and the house world was chosen because it was a more complex environment. A world that simulated the environment that the TB3B would eventually explore was not used as there was no world such as this already provided. It was decided that this was unnecessary workload as there are real-world environments at the university campus that satisfies our requirements.

| The ROS-graph used for navigating. | Screenshot of viewport in Rviz. | Captured frame of the camera feed. |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Figure 28 | Figure 29 | Figure 30 |

Cartographer was successfully implemented on the TB3B platform and the output of the online node was satisfyingly processed by the navigation stack. The local navigator that was created to ensure optimal distance from walls was tested in a real-world environment but the complete solution was only deployed in a simulated environment.

The robot has very good performance navigating unknown environments. The only problem was that the Local Navigator had some difficulties with rooms with a lot of furniture such as chairs and tables. The problem was that the controller could easily get confused and stuck in such environments. This is not considered an issue as it's not the environment that the robot is intended to work in.

As Cartographer is an approach to this dilemma, different approaches such as the Hector SLAM approach and Gmapping SLAM could have been tested. Due to the amount of time consumed to get to understand, implement and tune Cartographer, there would be insufficient time to do the rest.

Gazebo publishes an odometry frame. This was less than ideal to test SLAM algorithms in a realistic manner as the SLAM should solve this problem. It proved very difficult to disable the odometry frame from being published. Remapping the frame published from Cartographer also showed to have less than ideal results as nodes would not connect as they were expected to. The reason for this was not found.

As Cartographer is an approach to this dilemma, different approaches such as the Hector SLAM approach and Gmapping SLAM could have been tested. Due to the amount of time consumed to get to understand, implement and tune Cartographer, there would be insufficient time to do the rest.

Since Gazebo publishes an odometry source, the Cartographer odometry frame had to be blocked from being published. Doing otherwise resulted in errors with transforms. If the TB3B would be deployed in the real world, the Cartographer odometry frame could have been used in conjunction with an IMU frame to locate the TB3B as the odometry frame from Gazebo would not be present. How this would affect performance is not certain as no real-world tests were carried out with the complete solution.

The assumption was that the TB3B would navigate a completely flat 2D environment. This is of course not possible in the real world. For this reason, there might be performance issues with the solution in a real-world scenario. Ramp-like surfaces may lead to distortion in the mapping. No further investigation was put into the topic. Noise in sensor readings from the LiDAR may cause problems in a real-world scenario when executing SLAM. Cartographer has built-in filtering but no work was put into tuning the algorithm for it to reach its best performance. No testing was carried out to check whether the onboard inertial measurement unit (IMU) was sufficient enough for navigation purposes in the real world.

The data transfer method went through a couple revisions. Initially, the approach was to write a python script that would open python web sockets on each platform. The master node would then serve as a server and each robot would act as clients. Websockets are fairly intuitive to use and implement so it seemed like a good solution at first. After testing some issues became more clear. There are two big obstacles in the socket solution. Firstly it is down to multiprocessing, when you run a WebSocket it occupies the main process which blocks the robot from running any simultaneous processes. This can be solved in python by either running the script in a separate shell instance or by doing a multi-threading solution. Either way, it is sort of finicky to implement and the process tends to hang. That leads to the second issue of sockets. When the socket loses connection the entire process will hang. This is problematic when the robot will be able to reconnect it can not do so on the old socket process. Instead, the old process needs to be closed and then the script would have to handle the opening of an entirely new socket process. This flaw is just down to the implementation of the python WebSocket and it is not much that can be done to sidestep this issue. Lastly, using WebSockets would require a validation process. Essentially there needs to be a way to verify that each byte transferred reaches its location. To do this every byte received would have to be verified manually. In conclusion, the python WebSocket is not a great solution for a system that is prone to disconnecting and places a large importance on complete package transfers.

SCP (secure copy) is functionality that comes with any Unix based distro. This command comes in handy in this project because it allows for each robot to copy and send files to a remote location over an SSH connection. The issues that exist for python WebSockets are already handled in the SCP implementation. The only downside is that it doesn’t allow for continuous data transfer in a publish/subscribe model.

Getting all of the software properly installed and running took a lot of time in this project. This could have been avoided by having a better picture of what was needed in the beginning. There could have been more research in what should be done and added to the project.

The Raspberry Pi had some problems with handling the load and starting to overheat. A swap memory partition was reserved on the secondary memory to replicate RAM functionality when the primary memory is fully occupied. However, this was not enough if Rviz was running. So there would still be some issues with it being very slow and the heat.

The map merging had mixed results, as is visible in the final merge in Figure 23. It is however clear that the rotation part of the script is working as intended but the translation is not quite working. This is due to several problems, the first obvious issue it the fact that the research paper had additional steps in the calculation of the translation matrix that wasn't implemented due to time constraints. This included tuning it using image entropy with the histogram of the image, we are also not verifying the merged map.

Another issue is the maps we are using. If you look at Figure 15 and Figure 16 there are quite a few peaks which means that there is not a lot of information it can use to detect the transformations needed. In its current for it is simply comparing the longest walls to each other and since there are so few walls there are few data points to work with. If the maps were larger with more walls the result would most likely be more accurate.

As it stands the robot will not function automatically in our test environment. Further improvements would be to improve the shell script that automates a list of tasks. When a global navigation point has been given to the robot it will start moving. What the shell script needs to handle is the continuous updating of the global map known to each robot. This means that the script needs to run SCP commands to transfer the local map to the central station. Then there needs to be a script running on the central station which sends the global map back to the robot when a merge has been completed.

Currently, the robots explored by trying to reach a point set manually. An improvement would be to implement an algorithm that automates this process. The topic of automation opens up many interesting problems. One such problem is the multi-armed bandit problem[9]. The TB3B would have to compute which goal pose would result in the biggest benefit. Machine learning could provide solutions to this problem by recognizing patterns.

In the scenario where multiple TB3B robots are deployed, some form of swarm navigation would have to be performed, (YingTan & Zhong-yangZheng, 2013, p. 26-27) describes some concepts of robotic swarms that could become useful when designing such a system.

Another improvement would be to have the robots be able to communicate with each other to ensure that the area is explored as efficiently as possible. An interesting question would be, which TB3B should be trusted to be correct? A Byzantine generals problem[10] might occur if one or more of the TB3B robots provide the rest with faulty data. Some form of voting on which data to use would have to be carried out to not decrease the quality of the final result due to inconsistent information[11]. Additionally, some form of system to determine how trustworthy a robot has to be implemented to ensure that the faulty robots do not pass bad data in the voting procedure. In subterranean environments, there is also a challenge of whether to keep the robots close to each other and risk that they have to explore the same space, which would be inefficient, or to spread them out and risk that robots choose inefficient routes because they were unable to receive information of better routes.

Special thanks to Professor George Nikolakopoulos, PhD Student Christoforos Kanellakis, Senior Research Engineer Dariusz Kominiak and of course Associate Professor Jan van Deventer for their help and guidance.

When researching, the main points of the read article should be written down in the WIKI, this is in case someone else has to read up on the same thing. This means that they will not have to read the whole article to learn the main points, also if any important commands are included, they will be written down with a description of what they do.

In Git there is a strict workflow, nobody is allowed to push to the master branch, for example, the master branch is set to be protected, which means that the only way to add to it is by making new branches and creating pull requests. These pull requests have to be reviewed by at least two people, who if everything is good, will approve the pull request. When the pull request has two approved reviews it can be rebased and merged with the master branch. There is also an agreed-upon structure to the branch names where the name must describe loosely what they are for, for example, a branch named "patch-1" does not explain a lot, instead if it was called "#XX Implementing Cartographer". It first describes the issue related to the branch, and then an extremely short description of what the branch is used for.

|

|---|

| Figure 31 |

To build the entire system the plan at the moment is to use Jenkins, this is an open-source continuous integration program which means it is not directly used to build the system, but plugins can be used to add a build functionality depending on the language used. Jenkins is also a testing and reporting platform which means that it can automatically test the code after it is built.

All the meeting protocols can be found here.

[2] Sajad Saeedi, Liam Paull, Michael Trentini, Mae Seto, Howard Li. Map merging using hough peak matching. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6386114/citations#citations (2012), (Accessed: 01/11/2020)

[3] Open Robotics. “About ROS.” https://www.ros.org/about-ros/ (Accessed: 13/08/2020).

[6] Ros-visualization. "Rviz. https://github.com/ros-visualization/rviz (Accessed: 13/01/2020)"

[12] Cardona, Gustavo A.; Calderon, Juan M. 2019. "Robot Swarm Navigation and Victim Detection Using Rendezvous Consensus in Search and Rescue Operations." Appl. Sci. 9, no. 8: 1702.

[13] “Research Advance in Swarm Robotics.” Defence Technology 9, no. 1 (March 2013): 18–39. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221491471300024X?via=ihub.

[14] D7039E-E7032E. “Mapping-Robot.” https://github.com/D7039E-E7032E/Mapping-Robot (Accessed: 13/01/2020)