This project was developed to teach and learn the principles of memoization using React.

If you are not interested on knowing memoization and wants to know only about React.memo and how it was used in this project, go to the Project's Readme

To first understand the power that comes with React.memo, we have to be familiar with the term 'memoization'. This term was first used by Donald Michie, and comes from Latin from the word "memorandum" ("to be remembered"). That says a lot, right? In american english memoization often gets truncated as 'memo', which is how we know it.

To be simple, memoization remembers a lot something that we are already familiarized with: Caching. The reason of existance of caching is quite simple:

Avoid doing the same work repeatedly to avoid spending unnecessary running time or resources! Because we, the computer science guys are “lazy”.

The main difference between memoization and caching is that memo is the caching technique on the scope of a Function!.

Memoization is an optimization technique where expensive function calls are cached such that the result can be immediately returned the next time the function is called with the same arguments, with no need of recalculation.

To code your own memo function you can do something like this:

const simpleCache = {}

function sumInCache(a, b, c) {

let key = `${a}-${b}-${c}`;

if (key in simpleCache) return simpleCache[key];

const result = a + b + c;

Object.assign(simpleCache, { [key]: result });

return result;

}As you can see, we transform the parameters of sumInCache() to string and concatenate them to be the key of the cacheEmulator. So say, if we call 10000 times of sumInCache(1, 2, 3), the real calculation happens only the first time, the other 9999 times of calling just return the cached value in cacheEmulator, THAT'S FAST!

For now, we can easily think of 2 use cases to turn a function to its memoized version.

- If the function is pure and computation intensive and called repeatedly.

- If the function is pure and is recursive.

The first one is straightforward, it’s just simple caching, but it is super powerful. The second one is more interesting and we will explore it a little bit more now:

We will use the Fibonacci sequence to illustrate it.

function fibonacci(n) {

if (n === 0 || n === 1) {

return n;

}

return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2);

}That's the Fibonacci sequence recursively. We all are quite familiarized to it, but we also must know that, for bigger numbers, this code can be quite expensive because it's complexity is O(2^n).

O(2^n) denotes an algorithm whose growth doubles with each additon to the input data set. The growth curve of an O(2^n) function is exponential - starting off very shallow, then rising meteorically.

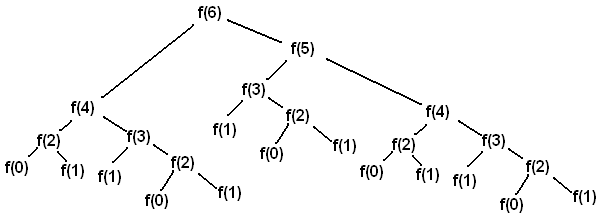

Okay, that's bad, so we can use our new (super powerful) weapon to neutralize it. Let's breakdown Fibonacci's code execution using a graph.

As we can see, there are some repeated calculations. For example, fibonacci(3) is computed 3 times, fibonacci(2) is computed 5 times, and so on so forth.

If we make fibonacci memoized, then we can guarantee for a number n, it’s fibonacci number will be calculated only once, this enhanced version of Fibonacci can be written like this:

const memo = (func) => {

const myCache = {};

return function () {

const key = JSON.stringify(arguments);

if (myCache[key]) return myCache[key];

const val = func.apply(this, arguments);

myCache[key] = val;

console.log(val);

return val;

}

}

const fib = memo(function(n) {

if (n < 2) return 1;

console.log('loading...');

return fib(n-2) + fib(n-1);

});After it the graph that we use to represent the Fibonacci sequence becomes something like this:

The function calls in the blue boxes have been already computed, so they are just skipped, which reduces the complexity to O(n) now! But, in the other hand, the space also becomes O(n).

Memoziation is beneficial when there are common subproblems that are being solved repeatedly. Thus we are able to use some extra storage to save on repeated computation. To choose for this trade-off is completely up to you.

While in some languages the developer must incorporate her/his own method of memoization, React has it's own.

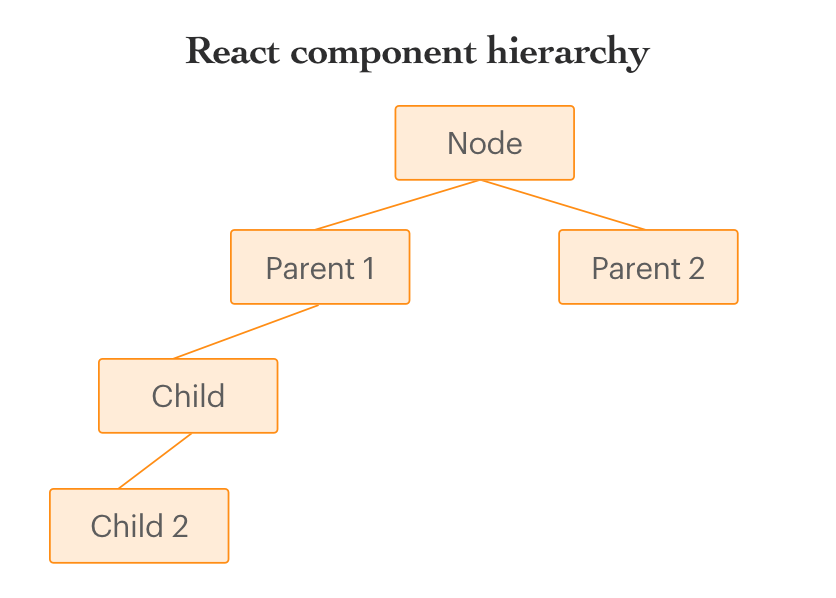

Imagine you have the following components tree in your project:

If, for some reason, the Parent 1 re-renders (maybe it's state changed because of an input or something), Child and Child 2 will also re-render, even if nothing changed on then. That's something that happens constantly in every React project, and that's fine if your App doesn't have this many components, but imagine having to re-render an entire Application just because you typed a single letter in an input. It isn't something to look forward, right?

When we used Classes in React, we've had the shouldComponentUpdate(), but it was super dangerous because it basically blocked the React's magic, which is to constantly re-render.

But you might say 'But nowadays, with React Hooks we have useMemo and useCallback', you're absolutely right, I was getting to this point just know:

First of all. this isn't a fight and you don't have to pick a side. You can use all 3 of them in a project, but it is important to know what you're doing and their differences.

In a basic way, the three of them do the same thing, but with different scope.

- React.memo memoizes an entire component, and is used like this:

import React, { memo } from "react";

function PostItem({ post }) {

return (

<li>

<h2>{post.title}</h2>

<p>{post.body}</p>

</li>

);

}

export default memo(PostItem);But, if the parent passes a non-primitive type as an array by props, it breaks.

- To resolve it, we use useMemo, which will memoize the value of an variable. So, we can do something like this:

import React, { useMemo } from "react";

import PostItem from "../PostItem/PostItem";

function PostList() {

const array = useMemo(() => {

return ["one", "two", "three"];

}, []);

return (

<ul>

<postItem array={array} />

</ul>

);

}

export default PostList;Similar to the useMemo, the useCallback works with functions, since they have the same syntax, we won't highlight an example here, but feel free to contribute if necessary.

Memoization is a great technique and should be used more often amongst developers. Since React has it's own methods, why not explore them and make a more beatiful and fast code?

But, even so it seems great (and it really is), it is important to know when and where to use, because an unnecessary memoization is as bad as not memoizing at all!

More generally consider using memoization only for those possibly frequently called functions whose arguments may appear the same repeatedly. And, in React, use the different methods only when you see a constant and unnecessary re-rendering, when using React.memo.