In this blog post, we will go through a formal STRIDE threat modeling session. There are multiple different approaches to threat modeling: threat modeling as code, software diagramming tools, threat modeling tools, ad-hoc unstructured threat modeling, and formal threat modeling using AWS Threat Grammar and STRIDE. The point is, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

In this blog post, I will be utilizing AWS Threat Grammar and STRIDE because I believe they are a good fit for threat modeling workflows. However, it's important to understand that the choice of approach should be based on the specific requirements and context of your project.

- Different kinds of threat models

- What to include in our threat model?

- Understanding the workflow

- How to build comprhensive threat models?

- Threat Actors

- Threats

- Mitigations

- Compliance

- Scaling our threat models

- The Application of AI in threat modelling

- Reusable Markdown version

Security engineers perform threat modeling on various scopes, such as systems of systems, infrastructure, cloud environments, applications, and microservices. The scope can range from extensive and high-level to specific functions. However, it's always worth conducting threat modeling for sensitive and critical functionalities, with checkout and payment functionalities being a prime target for threat modelling activities.

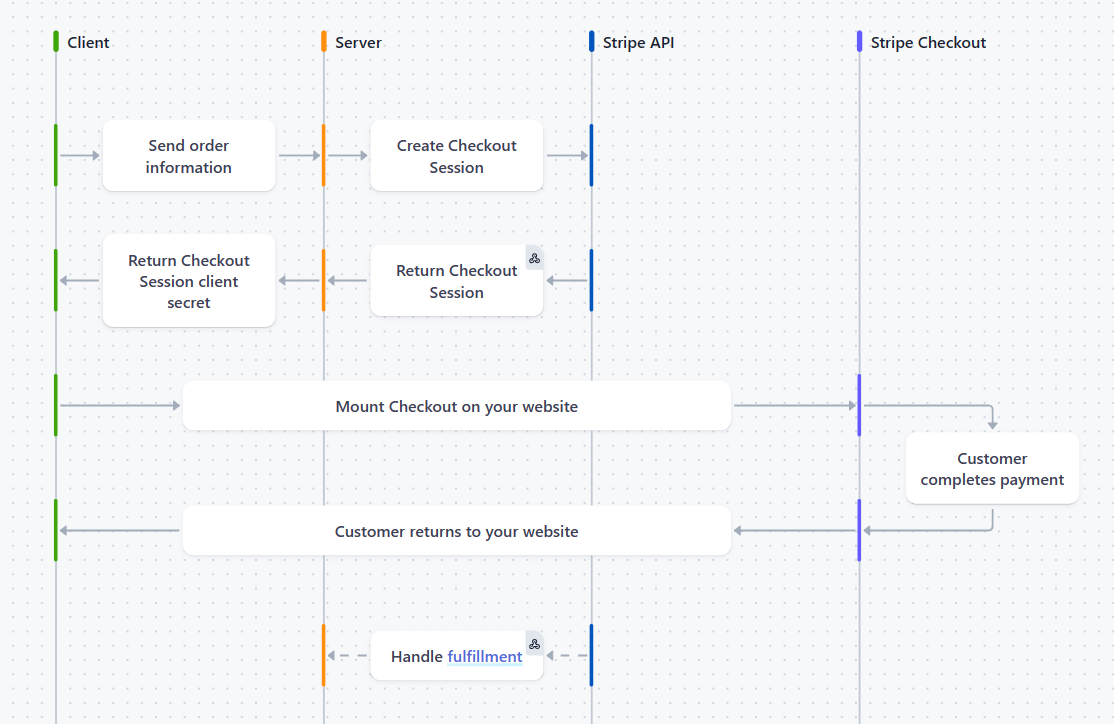

In our case, we've decomposed our threat model to focus on the smallest possible workflow. This makes it more reusable and accessible for as many developers as possible. Specifically, we'll be conducting threat modeling on one specific workflow: the cart checkout functionality using Stripe.

Our Checkout workflow does not exist in isolation. It is part of a larger application or group of microservices that customers interact with before they reach the checkout workflow. There is a shop functionality, an authentication/authorization system, a system used by support employees internally to resolve customer issues, a monitoring solution, and so on. All these functionalities and systems are directly or indirectly connected to our checkout functionality.

For the sake of reusability, we're focusing our threat modeling efforts on a specific workflow. Consequently, certain attacks from adjacent systems, applications, and microservices connected to our checkout feature are considered out-of-scope for this threat model.

For instance, let's consider a support system utilized by internal employees to assist customers with purchase inquiries, which might be directly linked to our checkout system. In such a scenario, if a support employee downloads cracked software onto their device, it could become infected. Subsequently, an adversary could exploit the infected support device to gain access to our cart logs and other sensitive data

You cannot threat model what you don't understand. Before my threat modeling session with the developers, I reviewed the official Stripe Checkout Documentation and explored the code snippets. Armed with a basic understanding of the workflow, I set myself up for success. This preparation allowed me to follow up during the meeting, ask informed questions, and engage in meaningful discussions with the team.

Here is an image from the official stripe documentation.

Defenders need to think about everything, while an attacker only needs to find one security issue to exploit our systems. So, how do you defend effectively?

For starters:

- Read the documentation: If possible, implement the workflow yourself to gain hands-on experience.

- Follow security best practices published by Stripe. Don’t reinvent the wheel—many smart people have contributed to these guidelines, so make good use of them.

- Communicate with your developers about the flow, risks, and mitigations. You'll be surprised by how their insights can help defend against threats or inspire you to identify additional vulnerabilities.

Those are the different threat actors targeting our system:

- External user

- Internal employee

- Malicious process running on the same host node

- Malicious NPM package contributor

- Malicious JavaScript library contributor

| Threat ID | Threat Statement |

|---|---|

| T01 | An internal employee with access to source code could exfiltrate the Stripe API keys, leading to unauthorized key use to enumerate customer data via Stripe APIs and/or perform fraudulent purchases at a reduced cost (e.g., $1 items). |

| T02 | An external actor could exploit Stripe test cards in the production environment if the engineering team inadvertently deploys test APIs/keys in production, resulting in financial loss. |

| T03 | An attacker could perform a supply chain attack on a JavaScript library on the frontend, leading to a compromise that allows the injection of malicious code or the exploitation of vulnerabilities in the Stripe checkout process. |

| T04 | An attacker could perform a supply chain attack on an npm package, leading to a compromise that allows the injection of malicious code into the microservice/application. |

| T05 | An attacker who discovers a misconfigured webhook handler path without authentication could exploit this to simulate purchases, resulting in financial loss. |

| T06 | A rogue process running on the node could intercept packets on their way to the webhook handler and replay the requests to initiate unauthorized purchases. |

| T07 | An external actor could leverage a race condition vulnerability to exceed the coupon limit during checkout, resulting in unauthorized discounts or financial loss. |

| T08 | An external actor could leverage a race condition vulnerability to add items to the cart while checking out at the same time, resulting in obtaining more items than they paid for. |

| T09 | An attacker could tamper with the data in transit between our webserver and Stripe if the connection is not secured using TLS, leading to potential data breaches or financial fraud. |

| T10 | A person could falsely claim they ordered an item they did not if proper auditing or logging is not in place, resulting in financial loss due to the inability to verify the claim. |

| Mitigation Number | Threats Mitigating | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| M-001 | T01 | Use HashiCorp Vault to store the Stripe keys, and fetch them at runtime. |

| M-002 | T02 | As part of our SAST scans, ensure the CI/CD pipeline fetches the Stripe keys that will be deployed and checks the prefix for live and test versions. Test keys are prefixed with: pk_test sk_test Live keys are prefixed with: pk_live sk_live |

| M-003 | T04 | Pin npm packages to specific versions, and perform regular scans in our CI/CD pipelines. |

| M-004 | T03 | Leverage the Subresource Integrity (SRI) security feature to ensure the cryptographic hash of a fetched resource matches the expected hash. |

| M-005 | T01 | Set IP restrictions on the Stripe keys to only allow the IP addresses of our servers from the Stripe management web portal. |

| M-006 | T01 | Implement role-based access control (RBAC) and audit logs to monitor and restrict who can access the Stripe API keys. |

| M-007 | T05 | Use the Stripe verification library to validate that webhook events originate from Stripe. More details at: Stripe Webhooks Documentation |

| M-008 | T06 | Handle duplicate events by making the app idempotent to ensure the same signed Stripe request cannot be replayed multiple times. |

| M-009 | T10 | Ensure all transactions are timestamped and logged, and save the last few characters returned by Stripe for each transaction. Note that logging is a significant topic in e-commerce that deserves its own write-up. |

| M-010 | T05 | Configure the webserver to block requests to the webhook process that are not received from Stripe IP addresses listed in the Stripe Webhooks Documentation. |

| M-011 | T02 | Leverage a DAST scan with the Stripe key used in production to ensure Stripe test cards cannot perform purchases in production. |

| M-012 | T07 | In the add coupon functionality, ensure checks are implemented at multiple locations in the code, for example, during the add coupon operation and again during the checkout operation to verify the number of coupons used. |

| M-013 | T07 | In the add coupon functionality, ensure checking operations and counter incrementing operations are performed before the coupon is applied. |

| M-014 | T08 | During the checkout process, copy the user's cart (cache the current cart) and use the cached version for all operations afterwards. |

| M-015 | T07 | During the checkout process, copy the user's coupons (cache the current coupons used) and use the cached version for all operations afterwards. |

| M-016 | T07, T08 | Leverage database locks and concurrency features to mitigate race conditions. |

| M-017 | T09 | Ensure TLS is enforced in production and that industry-standard secure ciphers are in use. |

Every organization has its own compliance needs, contractual obligations, third-party requirements, and more. The list is endless. As a security engineer, you must ensure your threat models address these needs. They are a crucial factor in your security features.

DISCLAIMER: This is not legal advice. The following information is for educational purposes only and should not be relied upon as legal or compliance advice. Please conduct your own due diligence.

In my case, the company was very small and did not have PCI requirements. However, I did some due diligence and discovered that Stripe requires customers using Stripe Checkout to complete the PCI SAQ A survey and submit it annually. After some back and forth with the Stripe team, I learned that Stripe Checkout customers might be eligible for an auto-generated survey provided by Stripe, which they can upload. So, for now, there are no compliance requirements for me. For now!! Always stay vigilant for changes in requirements and scope.

Given our threat model, I recommend documenting this in Confluence or your preferred internal documentation tool. If your organization is large enough, consider hosting AWS Threat Composer and importing these models into it. The whole point of decomposing threat models is reusability, so let's ensure these threat models can be utilized by other teams as well!

While GPT-4 could not generate a useful threat model, it often explained STRIDE or provided generic information about threat modeling.

That being said, it was very useful in ensuring the semantic and grammatical correctness of the threat model. Additionally, it rephrased the threats to comply with AWS threat grammar consistently. With a little bit of guidance, it was quite capable of identifying which mitigations blocked which threats.

If you are looking for a ready-to-use Markdown version, please check out the GitHub repository for this threat model at: Threat-Modeling-Stripe-checkout