We pose the problem of protein sequence design given a backbone structure as a node labeling problem and solve it with graph attention networks (GATs). We use a dataset of structurally non-redundant protein structures and implement graph representation and graph attention networks using PyTorch Geometric. In our experiments, GATs achieve perplexities < 5.0, similar to the reported perplexity for protein design algorithms in common use (such as ProteinMPNN), on held-out test data that is structurally dissimilar from training data.

One important application of the use of deep learning to protein design is the design of sequences conditioned on backbone structures. Sometimes referred to as "inverse folding", the problem of fixed-backbone protein design is the problem of designing a sequence that will fold into a particular backbone structure. The inputs to a deep-learning–based structure-conditioned protein design algorithms are structural coordinates, and the outputs are per-position logits over the 20 amino acids which can be sampled from to generate definite sequences. This procedure is similar to existing methods for fixed-backbone protein sequence design, such as Rosetta1. The game is to design sequences that, when expressed, fold corrected into the designed structure.

Empirically, structure-conditioned protein sequence design algorithms have been useful for designing stabilizing mutations 2, structure-guided diversification in design pipelines 3, and have recently been updated to include structural information from nucleic acids, small molecule ligands, and metal ions 4. They are routinely used to design sequences as part of de novo protein design pipelines 5. Many different implementations are available, with different properties, most largely based on the original implementation by John Ingraham 6.

For this project, I'd like to do something a little different. Graph attention networks, introduced by Veličković in 2017 7 and updated in 2021 by Brody 8, make use of an attention mechanism on the graph structure and are similar to the model developed by Ingraham, except simpler in that they do not have the autoregressive decoder. Here, we reimagine the problem of protein design as a node labeling problem on a graph that we build from the protein structure. Using PyG, we build a flexible and scalable graph attention network that learns from backbone coordinates by representing each designable residue or ligand as a node, with edge features derived from backbone atom distances. All of this is implemented in a straightforward and clean way in modern PyTorch.

All the code, including the model implementation, and the weights of the trained models, are available on GitHub. An overview of the code is as follows:

fetch_data.sh, script to download and unpack the training data into a folder calleddatatrain.py, main training scripttest.ipynb, evaluation notebook

After a run of train.py, you'll have the following structure:

data/splits.pt, a dictionary with the keys "train", "val", and "test", where the value for each is a list containing the identifier of each sample (in this case, the path to the PDB file)train_set.pt, the processed training data as tensorsval_set.pt, the processed validation data as tensorstest_set.pt, the processed test data as tensors

For our dataset, we'll follow Ingraham 2019 in using the CATH non-redundant domains dataset clustered at the 40% identity level. To construct training, validation, and test sets, we split the dataset after shuffling to 25,508 training examples, 3,188 validation examples, and 3,189 test examples. We reject input samples with more than 512 residues.

The graph representation of the protein structures, including ligands and cofactors, is as follows. Residues for which we wish to design the sequence are represented as nodes, with dihedral backbone features. For each node, we construct a neighbor graph using a configurable C⍺-C⍺ distance and maximum distance. Edges are represented as RBF-encoded distances to nearby alpha carbons.

Non-protein residues, such as small molecule ligands, metal ions, and cofactors, are first embedded atom-wise and then globally pooled to form a per-molecule representation which is then treated similarly to a residue.

- See

data.pyfor the definitionload_protein_graphwhich contains the function that reads a PDB file and returns a PyGDataobject

We provide the following introduction to graph attention networks (GATs) following Brody8. A directed graph

For the model architecture, we chose a graph attention network (GATv2) model as implemented in PyG9. In the GAT model, we input graph-structured data where each node is a residue for which we require a categorical label in the amino acid alphabet. Each training step, the network generates an updated representation RadiusGraph, with a maximum distance of 32.0 angstrom and a configurable maximum number (either 16 or 32 in this study). The updated node features

$$ h'i = \sum{} \alpha{i,j} W h_j $$

where

where the operation model.py for the model implementation.

For the experiments we report here, we use a single A10 GPU node from Lambda Labs (cost: $0.75/hour) with 32 CPU cores with a total of 250 GB memory and 1 NVIDIA A10 GPU with 40 GB memory.

To reproduce the install, create a virtual environment, install PyTorch 2.3.1 and CUDA 12.1 (these specific versions from this page), then PyTorch Geometric and the other packages.

On my Lambda Labs instance, I used this setup script:

# create virtual env

python -m venv .venv

source .venv/bin/activate

# install torch 2.3.1 with cuda 12.1 (since there's a pyg wheel for this combo)

python -m pip install torch==2.3.1 torchvision==0.18.1 torchaudio==2.3.1 --index-url https://download.pytorch.org/whl/cu121

# install pyg

python -m pip install torch_geometric

# install supporting libraries

python -m pip install torch_scatter torch_sparse torch_cluster torch_spline_conv -f https://data.pyg.org/whl/torch-2.3.0+cu121.html

# install other dependencies

python -m pip install biopython rich tb-nightly ipykernel Now you will have a nice virtual environment will all the dependencies and all the Torch and CUDA versions nicely lined up.

To reproduce the results here, there are only two steps. First, preprocess the dataset. Second, train the models. To preprocess the dataset:

python data.py This will create the files train_set.pt, val_set.pt, and test_set.pt, and splits.pt. These will be used by the train script. To run training, set your hyper parameters and then:

python train.py Model outputs and Tensorboard logs will be saved to the folder given by EXPR_NAME in the code (or the current date and time, if no experiment name is provided).

Warning: generated data files to train on all samples, with a neighborhood size of 32, are over 100 GB in size.

We conduct two sets of experiments. In the first set, we use features derived only from the coordinates of C⍺ atoms. In the second set, we expand our features to use pairwise distances between all four backbone atoms, while maintaining the RBF encoding. In all experiments, we use the same train, validation, and test samples and use a random seed for Python and Torch of 42 throughout for reproducibility.

In our first set of experiments, we build the protein feature graph using only the coordinates from alpha carbons. Node features (

| Model | Neighbors | Train perplexity | Validation perplexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform | 20.00 | 20.00 | |

| Structured Transformer 6 | 32 | 6.85 | |

| GAT d=64 | 16 | 6.55 | 6.62 |

| GAT d=128 | 16 | 6.30 | 6.36 |

| GAT c=256 | 16 | 6.17 | 6.30 |

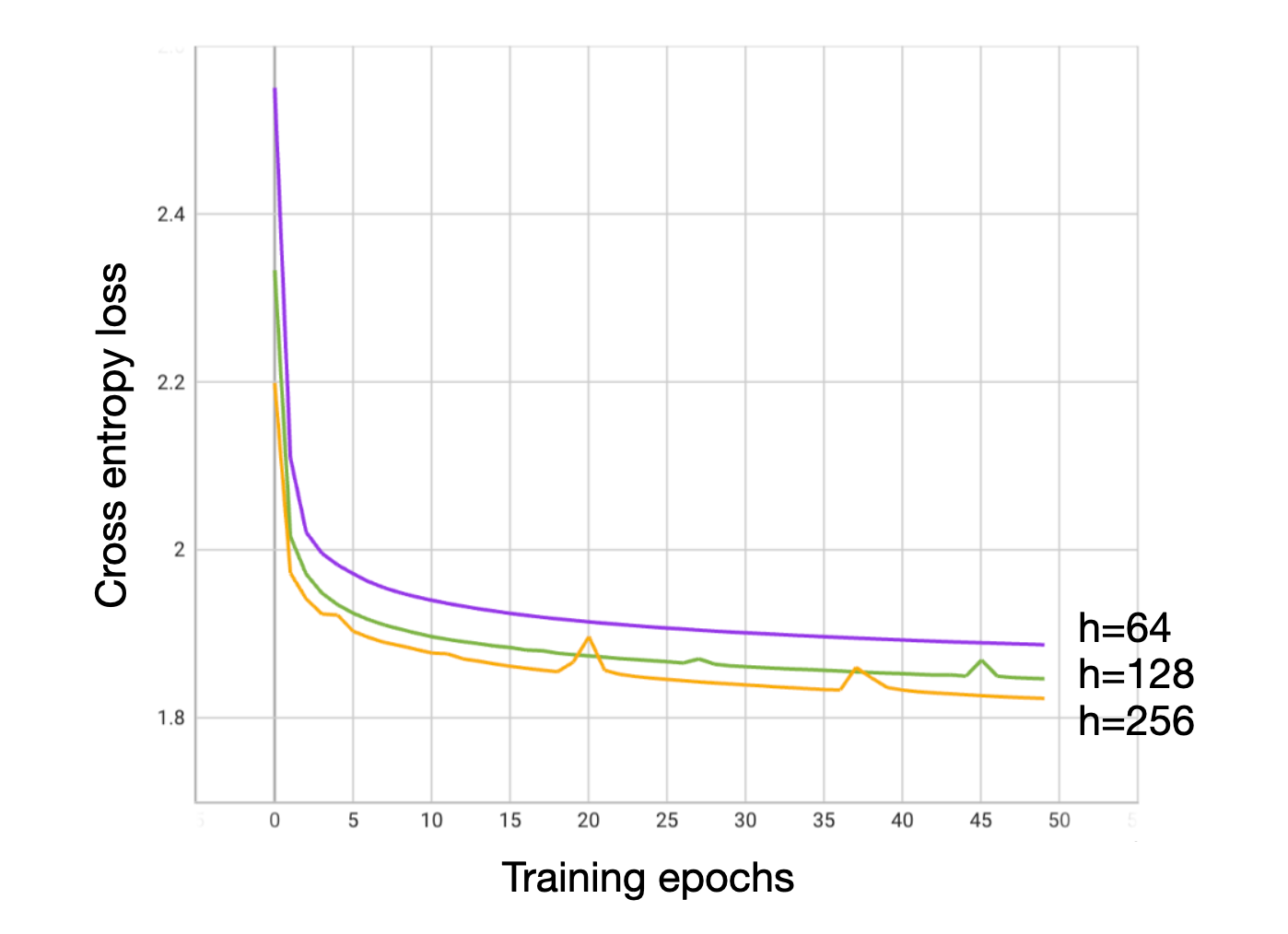

Table 1. Comparison of GAT with C⍺ features with a uniform model and an existing inverse folding model using C⍺ features from Ingraham. We compare the perplexity (given by exp(loss)) of different structure conditioned models. Intuitively, perplexity gives an idea of how many choices the model thinks are good at a specific position. Since we have a vocabulary size of 20, a perplexity of 20 represents total uncertainty, and smaller perplexities represent better accuracy. A uniform distribution gives a perplexity of 20. The Structured Transformer from Ingraham, trained on a similar (but not identical) dataset achieves a held-out test perplexity of 6.85 with C⍺ features and a model dimension of 128. Our GAT models trained for 50 epochs with model dimensions 64, 128, and 256 achieve similar, slightly lower perplexities in these experiments despite having half the number of layers. This indicates that GAT models may be useful at the task of protein design, and motivated further experiments.

Figure 1. Loss curves for training of GAT models with C⍺ features.

Our GAT models have a similar structure and similar size (in terms of number of parameters, model dimension) but also have some important differences with the Structured Transformer. First, the Structured Transformer adopts an encoder-decoder architecture where the decoder is provided access to the preceding elements in a sequence as it is being decoded. In our model, the representations for the nodes are updated simultaneously. We'll have to see if this plays a role in how good the models are when tasked with sequence design.

Some thoughts and ideas from this experiment using only alpha carbon coordinates:

- Would be sweet to also train Ingraham model on exact same data for a direct comparison

- Can we think of better node features to start out? Our node features of size 4 are projected up to the model dimension in the first layer, and are really not used. Can we set them to zero, like ProteinMPNN, and eliminate a lot of code?

- The parameters we can explore next are: can we add more backbone coordinates? Can we increase the number of layers? Can we increase the number of heads?

In order to build upon and extend the first experiment with coordinates provided only by alpha carbons, we next sought to increase the representational capacity of our model. To do this, we created a new feature representation including N, CA, C, and O backbone atom distances, which are RBF encoded.

| Model | Feature set | Layers | Neighbors | Train epochs | Train perplexity | Val perplexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | C⍺ only | 3 | 16 | 50 | 6.30 | 6.36 |

| E2 | All backbone atoms | 3 | 16 | 50 | 5.93 | 5.99 |

| E3 | All backbone atoms | 6 | 16 | 50 | 5.64 | N.E. |

| E4 | All backbone atoms | 6 | 32 | 50 | 5.36 | N.E. |

| E3 | All backbone atoms | 6 | 16 | 150 | 5.21 | 5.40 |

| E4 | All backbone atoms | 6 | 32 | 150 | 4.90 | 5.19 |

Table 2. Comparison of GAT models with C⍺ features and all backbone atom features at different model sizes. Training and held-out evaluation loss for four GAT models trained to explore the effect of different features and model sizes. For E1, we use the h=128 model from the first set of experiments. For E2, we add RBF-encoded N, C, and O features to the existing RBF-encoded CA features via concatenation. For E3, we deepen the model to 6 layers (from 3). In E4, we increase the neighborhood size to 32 and also add gradient clipping to smooth out the loss over training.

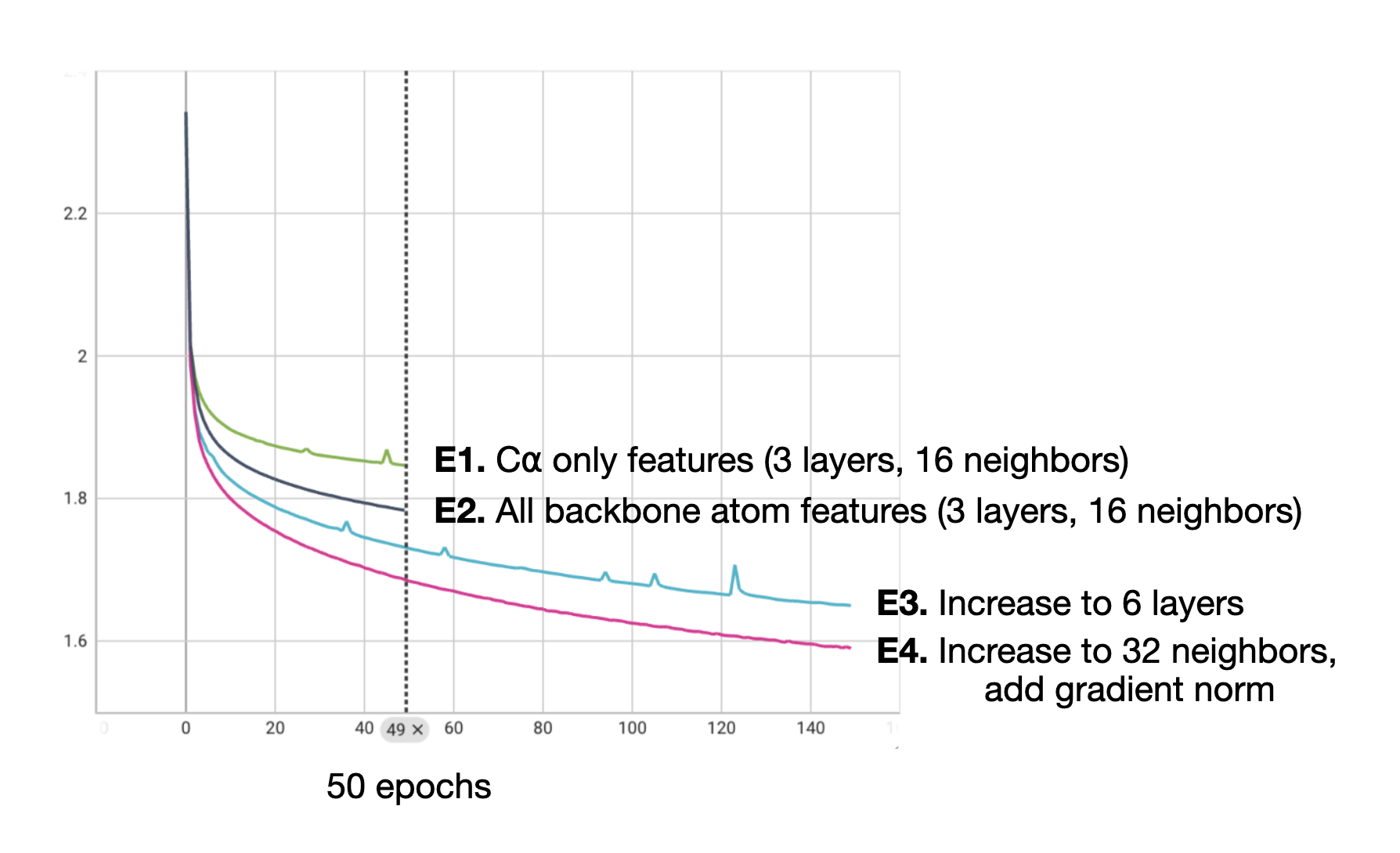

We observed decreased cross entropy loss (decreased perplexity) on our held-out set of protein structures via the addition of features derived from the N, C, and O atoms in addition to the CA atoms we were already using for the model that we termed E2. As a baseline, we used the best model from the previous set of experiments with model dimension 128 as E1.

For the next model, E3, we simply deepened the model by increasing the number of layers to 6. For E4, we increase the neighborhood size. After we observed during the training of E3 continued training instability, we also implemented gradient clipping for the training of E4. Empirically, this appears to have helped as the training curve for the E4 model is notably smoother.

Figure 2. Training curves for four GAT with C⍺ features and all backbone atom features at different model sizes. Training loss for four GAT models trained to explore the effect of different features and model sizes. For E1, we use the h=128 model from the first set of experiments. For E2, we add RBF-encoded N, C, and O features to the existing RBF-encoded CA features via concatenation. For E3, we deepen the model to 6 layers (from 3). In E4, we increase the neighborhood size to 32 and also add gradient clipping to smooth out the loss over training.

Here, we have shown how we can use graph attention networks for protein design. Through experiments with a structurally non-redundant dataset of protein structures, we have shown that even small graph attention networks (around 1 M params) are able to achieve perplexity of near 5.0 on more than 3,000 held out test structures that are structurally dissimilar to the structures used for training, indicating that our models have learned to generalize.

We have sampled some of the hyper parameter space in our experiments, and suggest a few lines of thought for future work:

- Tune hyper parameters: I'd like to experiment with learning rate, and try the

TransformerConvlayer. Also, we should explore expanding the number of heads, instead of the number of layers. - Evaluate the models' ability to design new sequences using the provided

generate_sequencefunction, we leave for a Part 2. - Evaluate some designed sequences in the lab