This project is currently not under active development for the time being. Linear Attention doesn't particularly seem like a promising research area for the future of AI, this was certainly a fun project though!

This project implements a novel linear attention mechanism based on "softmax-weighted cumulative sums" which has surprisingly favorable properties in computational complexity, explainability, and theoretical expressiveness. This project strongly believes that this linear attention mechanism can replace full attention with virtually no tradeoffs, if not actually having even better performance (because it's a more simple attention mechanism). This was originally inspired by adapting Fastformer: Additive attention can be all you need by Wu et al. (2021) (where they don't use any kind of cumulative sum) for causal language modeling which we also implement with documentation and a comprehensive README that can be found in src/leap/fastformerLM.

Reasons why LEAP may be able to replace full attention:

-

The models considered in this project run faster than a standard Transformer of the same size even on small sequence lengths (the math allows for highly parallelizeable operations which is not always the case with linear attention) which offers high ease of use

-

Linear in time local attention, this concept has not been seen before in the literature as local attention typically has to scale in time complexity with the size of the local window. This project uses some simple mathematics and reuse of computations to get around this (and still be parallelizeable). This gets around the issue that longer sequences will typically need bigger local attention windows, but also builds upon the surprising strength of local + global attention (previously explored in Longformer and BigBird with the addition of random attention).

-

Built-in Explainability, while explainability is not supported yet in this project, each token will be assigned an "focus weight" (which is softmaxed over the sequence) that can be used to explain what tokens the model is paying attention to, and which tokens are ignored. This is similar to the explainability offered by the original Attention is All you Need paper, though more simplified

-

O(1) Path Length/Flexibility, A great strength of full attention Transformers is the flexibility provided by the

$O(1)$ path length. An example where many linear attention mechanisms would likely fail (ie. if they only use local/convolutional attention or time-decaying factors or a recurrent vector that will get overloaded with information over time) would be when there is "task metadata" at the beginning of the sequence. Example: "Read the following story paying special attention to how Alice treats Bob as you will write an essay on this after: <very long story here>". This task information may not make it all the way through the story and writing the essay with the previously mentioned approaches, but with this project's approach, tokens from the beginning of the sequence can directly transfer information to tokens at the end of the sequence with a$O(1)$ path length (like full-attention) through global LEAP -

O(1) Inference, the math of LEAP can be represented as an RNN (while still maintaining the

$O(1)$ path length). Thus, you only need the previous token's embeddings (i.e.$O(1)$ space) to calculate the next token (as per being an RNN) which only takes$O(1)$ computations with no matrix-matrix operations (all with respect to sequence length holding model size/dimension constant). This was originally shown in Transformers are RNNs by Katharpoulos et al. (2020) to increase inference time performance by thousands of times and could potentially allow large language models to run on edge devices like mobile phones or consumer laptops!

Use the package manager pip to install (make sure you have pytorch installed with CUDA as a prerequisite)

pip install leap-transformerThen to use in python (setting the config how you want):

from leap import LeapForCausalLM, LeapConfig

config = LeapConfig(

hidden_size = 128, # size of embeddings

vocab_size = 32100, # number of tokens

n_positions = 2048, # max number of tokens to process at once

n_layer = 6, # how many stacked decoder layers to use

use_local_att = True, # whether to use windowed/local LEAP

window_sizes = None, # window sizes to use for windowed/local LEAP for each layer (set automatically if None)

n_head = 4, # number of heads to use in multi-head attention

initializer_range = None, # variance for weight initialization, defaults to 1 / sqrt(hidden_size)

hidden_dropout_prob = .1, # dropout value used for embeddings, attention, and feedforward layers

rescale = 10 # what to rescale the focus values with, set lower if you have unstable/NaN loss

)

model = LeapForCausalLM(config)

# this model is compatible with huggingface and its "trainer" interface

from transformers import Trainer

trainer = Trainer(

model = model,

args = <YOUR TRAINING ARGS>,

train_dataset = <YOUR TOKENIZED DATASET>,

...<YOUR OTHER TRAINER ARGS>

)

trainer.train()A more complete training example with a dataset, tokenization, and evaluations can be found at FastLM.ipynb in this repository which can be run with only 6GB of VRAM (GPU memory).

Use these installation instructions so that you will have the latest repo and your edits will be reflected when you run the code

git clone https://github.com/mtanghu/LEAP.git

cd LEAP

pip install -e .The math tricky and overly verbose/complicated at the moment but can be found in this repo with a write-up here. As stated the general concept is just to have a cumulative sum of the sequence that is weighted with values that are passed through a softmax over the sequence length (done causally though). What will be described here are just some high level details.

Cumulative sums were used reasonably successfully in previous linear attention mechanisms like Linear Transformers though they don't use the parallel cumulative sum that can be run in logarithmic time (w.r.t. sequence length) as noted by Performer. This can be seen in the following circuit diagram (from wikipedia prefix sum page). This means that a model of this kind could actually proportionally run faster on longer sequences (i.e. doubling the sequence length only increases the wall time by less than double).

Where each wire represents an element in the sequence as input (coming from the top) and where the output of each wire the cumulative sum up to that element in the sequence. Luckily this is already implemented by CUDA as seen here where they report that the cumulative sum operation runs about as fast as copying! What might set this off as being a good choice for sequence modelling is how the diagram almost shows a kind of "residual connections through time" in a way that seems vaguely neural.

The concept for LEAP is just to weight each element in the sequence before cumulative summing as a kind of "attention" or "focus". This implemented in a multihead way with queries, keys, and values and is meant to be something of an analog to full attention.

Because this is a causal language model the code is structured like one and implements the following to be fair comparison against GPT2 paper for reference by Radford et al. (2019) where LEAP just replaces the scaled-dot product Attention module in a Transformer:

- Pre-norming with a layernorm before projecting to token logits like GPT2

- GELU activation is used in the feedforward layer like GPT2

- Learned positional embeddings as per GPT1 paper by Radford et al. (2018) which carries over to GPT2 (though Rotary embeddings were considered, but decided against because it would unfairly give an advantage to the model when compared against normal Transformers/gpt2 which uses learned absolute positional embeddings. Just as a note, positional embeddings are still "needed" as a cumulative sum would not necessarily encode position information.

- Weight tying (Press & Wolf 2017) also used by Attention is All you Need, GPT1 and likewise GPT2

-

Multihead Attention where LEAP is simply performed on down projected vectors of size

$d_{model} \over n_{heads}$ in parallel with the same number of parameters as a single-head also as per Attention is All you Need by Viswani et al. (2017) which is carried over to GPT2 - The only slight difference is that biases are not used in the attention projection like PALM as it fits with the theme of the rescaled dot-product (to keep pre-attention logits low) for increased training stability. This shouldn't affect modeling performance much (if not decreasing performance) in the comparison against GPT2

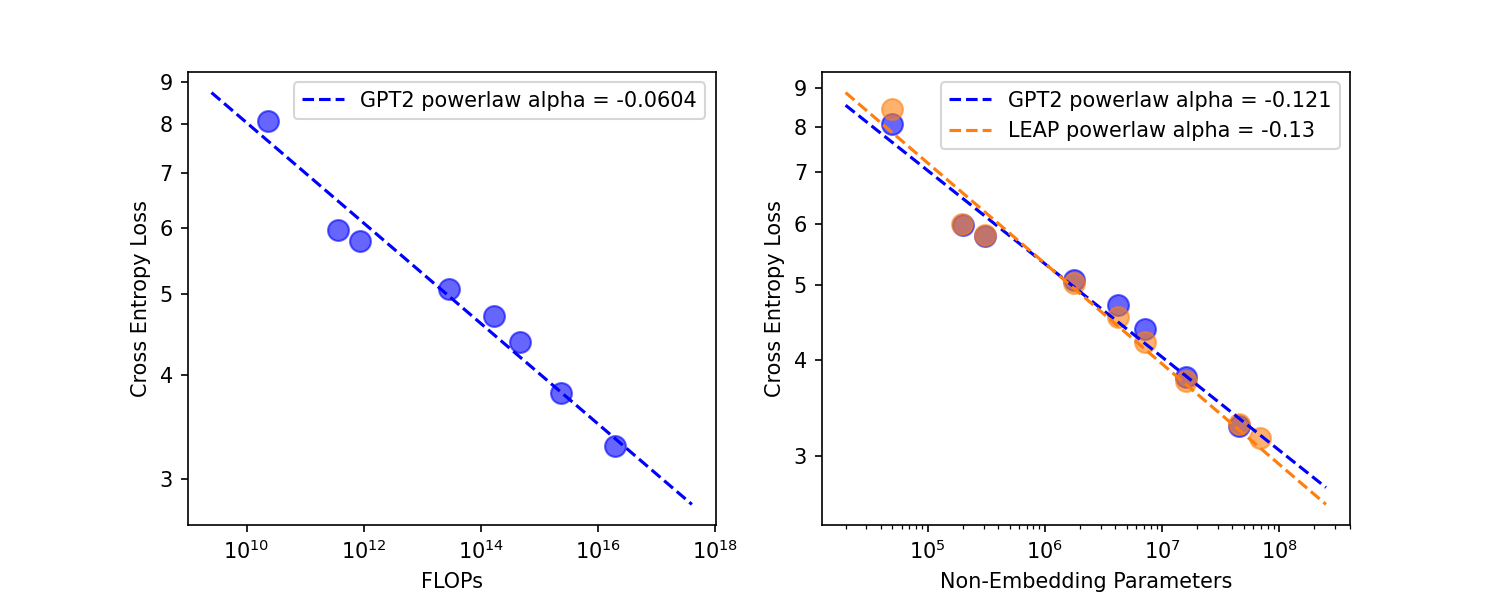

Following landmark papers Scaling laws for neural language models which has been revisited by Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models we hope to show the scaling behavior of LEAP and how it's quite comparable to a vanilla Transformer like GPT2. Note that as found by Scaling Laws vs Model Architectures, few to no models can match the scaling performance of Transformers. The experiment shown are done on much less data and much less compute, but at least preliminarily show LEAP's capabilities.

The compute scaling law (left) is in line with Scaling laws for neural language models which reported a alpha/exponent of around -.05 which should reasonably validate this experimental setup where FLOPs are estimated the same way. Note that if the FLOPs approximation used was applied to LEAP (where the sequence length quadratic complexity is just ignored) than LEAP would just use the same amount of FLOPs as GPT2 on equivalently sized models and dataset size.

The compute scaling law (left) is in line with Scaling laws for neural language models which reported a alpha/exponent of around -.05 which should reasonably validate this experimental setup where FLOPs are estimated the same way. Note that if the FLOPs approximation used was applied to LEAP (where the sequence length quadratic complexity is just ignored) than LEAP would just use the same amount of FLOPs as GPT2 on equivalently sized models and dataset size.

The parameters scaling law (right) has a higher alpha that what is reported in Scaling laws for neural language models of -.076 because data and parameters were scaled in tandem (for speed and also to be closer to compute optimal). Only non-embedding parameters are reported following Scaling laws for neural language models especially because the embedding parameters were a very significant proportion of the parameters. Following Scaling Laws vs Model Architectures, this test is meant to robustly compare a rather "exotic" architecture like LEAP to vanilla Transformers especially as "exotic" architectures can often get away with just having their hyperparameters/architectures tuned to match vanilla Transformer performance while not having the highly desirable scaling potential.

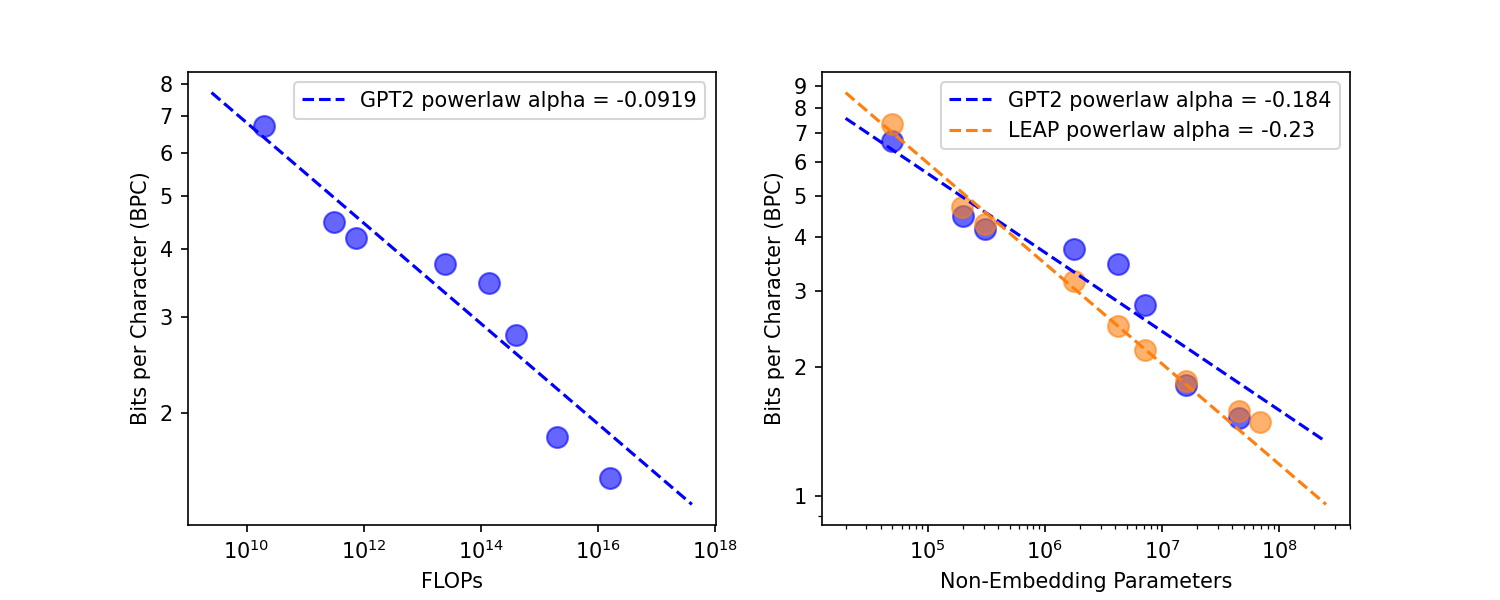

We try a similar test on the byte-level Enwik8 dataset to see if results transfer. Scaling laws are typically not studied for byte-level datasets (since tokenizers are generally more effective than either byte-level or word-level especially in terms of compute efficiency).

Again we see LEAP about matches GPT2, though there does seem to be some "bending" of the curve on the two largest tests for LEAP. This is concerning though bigger tests will have to be done to get a conclusive answer. Especially given how noisy this test seems to be (the GPT2 curve is completely wild). Note that the results shown have higher loss compared to the paperswithcode enwik8 leaderboard due to only training for a single epoch (meant to evaluate scaling potential and not peak performance).

Again we see LEAP about matches GPT2, though there does seem to be some "bending" of the curve on the two largest tests for LEAP. This is concerning though bigger tests will have to be done to get a conclusive answer. Especially given how noisy this test seems to be (the GPT2 curve is completely wild). Note that the results shown have higher loss compared to the paperswithcode enwik8 leaderboard due to only training for a single epoch (meant to evaluate scaling potential and not peak performance).

Exact training details and logs can be found in /Experiments/Scaling.ipynb of this notebook.

- Dataset: subsets of Wikitext-103 so that the number of tokens would match the recommendation of Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models where the (# parameters) is directly proportional to the (# tokens). The largest test uses the shown in the figure does use the entirety of Wikitext-103. All the same is true for the enwik8 dataset just that the test and validations splits are created manually at a random 5% of the data each

- Tokenizer a word-level tokenizer was used, but due to memory and compute constraints, the vocab size was limited to 8192. This means that the losses shown cannot be directly compared to Wikitext-103 benchmarks, but shouldn't particularly change scaling behavior. The enwik8 test resolves this by just using a normal byte-level tokenizer

- Hyperparameters: LEAP uses all the same hyperparameters as GPT2, all of which were chosen to be advantageous to GPT2 and not LEAP (likely better hyperparameters can be found for LEAP). We use a layer number ratio according to Levine 2020 that are best for Transformers like GPT2, and head size as close to 64 as possible. LEAP introduces local attention size as hyperparameters, though they were set automatically based on preliminary testing and not tuned (they don't seem to strongly affect performance either)

- Training: Training was performed for only 1 epoch on sequence lengths of 1024 (by splitting and concatenating articles) with cosine learning rate schedule with a warmup ratio of .05. This is all in line with Scaling laws for neural language models. The batch sizes were very small of just 2 because of memory constraints

Finer details: AdamW optimizer with default configuration and learning rate of 5e-4 (after warmup and is cosine annealed). No dropout or label smoothing for regularization was used due to only training for 1 epoch as per the recommendation of One Epoch Is All You Need

Wu, C., Wu, F., Qi, T., Huang, Y., & Xie, X. (2021). Fastformer: Additive attention can be all you need. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.09084.

Wolf, T., Debut, L., Sanh, V., Chaumond, J., Delangue, C., Moi, A., ... & Rush, A. M. (2019). Huggingface's transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.03771.

Beltagy, I., Peters, M. E., & Cohan, A. (2020). Longformer: The long-document transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.05150.

Zaheer, M., Guruganesh, G., Dubey, K. A., Ainslie, J., Alberti, C., Ontanon, S., ... & Ahmed, A. (2020). Big bird: Transformers for longer sequences. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 17283-17297.

Chowdhery, A., Narang, S., Devlin, J., Bosma, M., Mishra, G., Roberts, A., ... & Fiedel, N. (2022). Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.02311.

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2018). Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805.

Pérez, J., Marinković, J., & Barceló, P. (2019). On the turing completeness of modern neural network architectures. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.03429.

Katharopoulos, A., Vyas, A., Pappas, N., & Fleuret, F. (2020, November). Transformers are rnns: Fast autoregressive transformers with linear attention. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 5156-5165). PMLR.

Bahdanau, D., Cho, K., & Bengio, Y. (2014). Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473.

Radford, A., Wu, J., Child, R., Luan, D., Amodei, D., & Sutskever, I. (2019). Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog, 1(8), 9.

Müller, R., Kornblith, S., & Hinton, G. E. (2019). When does label smoothing help?. Advances in neural information processing systems, 32.

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., ... & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30.

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., & Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving language understanding by generative pre-training.

Press, O., & Wolf, L. (2016). Using the output embedding to improve language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1608.05859.

Kaplan, Jared, et al. "Scaling laws for neural language models." arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361 (2020).

Choromanski, Krzysztof, et al. "Rethinking attention with performers." arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.14794 (2020).

Komatsuzaki, A. (2019). One epoch is all you need. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.06669.

Loshchilov, I., & Hutter, F. (2017). Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101.