-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 115

Commit

This commit does not belong to any branch on this repository, and may belong to a fork outside of the repository.

Merge branch 'main' into hr/fix_benchmarks

- Loading branch information

Showing

5 changed files

with

618 additions

and

18 deletions.

There are no files selected for viewing

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| Original file line number | Diff line number | Diff line change |

|---|---|---|

| @@ -0,0 +1,77 @@ | ||

| #src # Changing Trixi.jl itself | ||

|

|

||

| # If you plan on editing Trixi.jl itself, you can download Trixi.jl locally and run it from | ||

| # the cloned directory. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| # ## Cloning Trixi.jl | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| # ### Windows | ||

|

|

||

| # If you are using Windows, you can clone Trixi.jl by using the GitHub Desktop tool: | ||

| # - If you do not have a GitHub account yet, create it on | ||

| # the [GitHub website](https://github.com/join). | ||

| # - Download and install [GitHub Desktop](https://desktop.github.com/) and then log in to | ||

| # your account. | ||

| # - Open GitHub Desktop, press `Ctrl+Shift+O`. | ||

| # - In the opened window, paste `trixi-framework/Trixi.jl` and choose the path to the folder where | ||

| # you want to save Trixi.jl. Then click `Clone` and Trixi.jl will be cloned to your computer. | ||

|

|

||

| # Now you cloned Trixi.jl and only need to tell Julia to use the local clone as the package sources: | ||

| # - Open a terminal using `Win+r` and `cmd`. Navigate to the folder with the cloned Trixi.jl using `cd`. | ||

| # - Create a new directory `run`, enter it, and start Julia with the `--project=.` flag: | ||

| # ```shell | ||

| # mkdir run | ||

| # cd run | ||

| # julia --project=. | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # - Now run the following commands to install all relevant packages: | ||

| # ```julia | ||

| # using Pkg; Pkg.develop(PackageSpec(path="..")) # Tell Julia to use the local Trixi.jl clone | ||

| # Pkg.add(["OrdinaryDiffEq", "Plots"]) # Install additional packages | ||

| # ``` | ||

|

|

||

| # Now you already installed Trixi.jl from your local clone. Note that if you installed Trixi.jl | ||

| # this way, you always have to start Julia with the `--project` flag set to your `run` directory, | ||

| # e.g., | ||

| # ```shell | ||

| # julia --project=. | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # if already inside the `run` directory. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| # ### Linux | ||

|

|

||

| # You can clone Trixi.jl to your computer by executing the following commands: | ||

| # ```shell | ||

| # git clone [email protected]:trixi-framework/Trixi.jl.git | ||

| # # If an error occurs, try the following: | ||

| # # git clone https://github.com/trixi-framework/Trixi.jl | ||

| # cd Trixi.jl | ||

| # mkdir run | ||

| # cd run | ||

| # julia --project=. -e 'using Pkg; Pkg.develop(PackageSpec(path=".."))' # Tell Julia to use the local Trixi.jl clone | ||

| # julia --project=. -e 'using Pkg; Pkg.add(["OrdinaryDiffEq", "Plots"])' # Install additional packages | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # Note that if you installed Trixi.jl this way, | ||

| # you always have to start Julia with the `--project` flag set to your `run` directory, e.g., | ||

| # ```shell | ||

| # julia --project=. | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # if already inside the `run` directory. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| # ## Additional reading | ||

|

|

||

| # To further delve into Trixi.jl, you may have a look at the following introductory tutorials. | ||

| # - [Introduction to DG methods](@ref scalar_linear_advection_1d) will teach you how to set up a | ||

| # simple way to approximate the solution of a hyperbolic partial differential equation. It will | ||

| # be especially useful to learn about the | ||

| # [Discontinuous Galerkin method](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discontinuous_Galerkin_method) | ||

| # and the way it is implemented in Trixi.jl. | ||

| # - [Adding a new scalar conservation law](@ref adding_new_scalar_equations) and | ||

| # [Adding a non-conservative equation](@ref adding_nonconservative_equation) | ||

| # describe how to add new physics models that are not yet included in Trixi.jl. | ||

| # - [Callbacks](@ref callbacks-id) gives an overview of how to regularly execute specific actions | ||

| # during a simulation, e.g., to store the solution or adapt the mesh. |

268 changes: 268 additions & 0 deletions

268

docs/literate/src/files/first_steps/create_first_setup.jl

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| Original file line number | Diff line number | Diff line change |

|---|---|---|

| @@ -0,0 +1,268 @@ | ||

| #src # Create first setup | ||

|

|

||

| # In this part of the introductory guide, we will create a first Trixi.jl setup as an extension of | ||

| # [`elixir_advection_basic.jl`](https://github.com/trixi-framework/Trixi.jl/blob/main/examples/tree_2d_dgsem/elixir_advection_basic.jl). | ||

| # Since Trixi.jl has a common basic structure for the setups, you can create your own by extending | ||

| # and modifying the following example. | ||

|

|

||

| # Let's consider the linear advection equation for a state ``u = u(x, y, t)`` on the two-dimensional spatial domain | ||

| # ``[-1, 1] \times [-1, 1]`` with a source term | ||

| # ```math | ||

| # \frac{\partial}{\partial t}u + \frac{\partial}{\partial x} (0.2 u) - \frac{\partial}{\partial y} (0.7 u) = - 2 e^{-t} | ||

| # \sin\bigl(2 \pi (x - t) \bigr) \sin\bigl(2 \pi (y - t) \bigr), | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # with the initial condition | ||

| # ```math | ||

| # u(x, y, 0) = \sin\bigl(\pi x \bigr) \sin\bigl(\pi y \bigr), | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # and periodic boundary conditions. | ||

|

|

||

| # The first step is to create and open a file with the .jl extension. You can do this with your | ||

| # favorite text editor (if you do not have one, we recommend [VS Code](https://code.visualstudio.com/)). | ||

| # In this file you will create your setup. | ||

|

|

||

| # To be able to use functionalities of Trixi.jl, you always need to load Trixi.jl itself | ||

| # and the [OrdinaryDiffEq.jl](https://github.com/SciML/OrdinaryDiffEq.jl) package. | ||

|

|

||

| using Trixi | ||

| using OrdinaryDiffEq | ||

|

|

||

| # The next thing to do is to choose an equation that is suitable for your problem. To see all the | ||

| # currently implemented equations, take a look at | ||

| # [`src/equations`](https://github.com/trixi-framework/Trixi.jl/tree/main/src/equations). | ||

| # If you are interested in adding a new physics model that has not yet been implemented in | ||

| # Trixi.jl, take a look at the tutorials | ||

| # [Adding a new scalar conservation law](@ref adding_new_scalar_equations) or | ||

| # [Adding a non-conservative equation](@ref adding_nonconservative_equation). | ||

|

|

||

| # The linear scalar advection equation in two spatial dimensions | ||

| # ```math | ||

| # \frac{\partial}{\partial t}u + \frac{\partial}{\partial x} (a_1 u) + \frac{\partial}{\partial y} (a_2 u) = 0 | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # is already implemented in Trixi.jl as | ||

| # [`LinearScalarAdvectionEquation2D`](@ref), for which we need to define a two-dimensional parameter | ||

| # `advection_velocity` describing the parameters ``a_1`` and ``a_2``. Appropriate for our problem is `(0.2, -0.7)`. | ||

|

|

||

| advection_velocity = (0.2, -0.7) | ||

| equations = LinearScalarAdvectionEquation2D(advection_velocity) | ||

|

|

||

| # To solve our problem numerically using Trixi.jl, we have to discretize the spatial | ||

| # domain, for which we set up a mesh. One of the most used meshes in Trixi.jl is the | ||

| # [`TreeMesh`](@ref). The spatial domain used is ``[-1, 1] \times [-1, 1]``. We set an initial number | ||

| # of elements in the mesh using `initial_refinement_level`, which describes the initial number of | ||

| # hierarchical refinements. In this simple case, the total number of elements is `2^initial_refinement_level` | ||

| # throughout the simulation. The variable `n_cells_max` is used to limit the number of elements in the mesh, | ||

| # which cannot be exceeded when using [adaptive mesh refinement](@ref Adaptive-mesh-refinement). | ||

|

|

||

| # All minimum and all maximum coordinates must be combined into `Tuples`. | ||

|

|

||

| coordinates_min = (-1.0, -1.0) | ||

| coordinates_max = ( 1.0, 1.0) | ||

| mesh = TreeMesh(coordinates_min, coordinates_max, | ||

| initial_refinement_level = 4, | ||

| n_cells_max = 30_000) | ||

|

|

||

| # To approximate the solution of the defined model, we create a [`DGSEM`](@ref) solver. | ||

| # The solution in each of the recently defined mesh elements will be approximated by a polynomial | ||

| # of degree `polydeg`. For more information about discontinuous Galerkin methods, | ||

| # check out the [Introduction to DG methods](@ref scalar_linear_advection_1d) tutorial. | ||

|

|

||

| solver = DGSEM(polydeg=3) | ||

|

|

||

| # Now we need to define an initial condition for our problem. All the already implemented | ||

| # initial conditions for [`LinearScalarAdvectionEquation2D`](@ref) can be found in | ||

| # [`src/equations/linear_scalar_advection_2d.jl`](https://github.com/trixi-framework/Trixi.jl/blob/main/src/equations/linear_scalar_advection_2d.jl). | ||

| # If you want to use, for example, a Gaussian pulse, it can be used as follows: | ||

| # ```julia | ||

| # initial_conditions = initial_condition_gauss | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # But to show you how an arbitrary initial condition can be implemented in a way suitable for | ||

| # Trixi.jl, we define our own initial conditions. | ||

| # ```math | ||

| # u(x, y, 0) = \sin\bigl(\pi x \bigr) \sin\bigl(\pi y \bigr). | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # The initial conditions function must take spatial coordinates, time and equation as arguments | ||

| # and returns an initial condition as a statically sized vector `SVector`. Following the same structure, you | ||

| # can define your own initial conditions. The time variable `t` can be unused in the initial | ||

| # condition, but might also be used to describe an analytical solution if known. If you use the | ||

| # initial condition as analytical solution, you can analyze your numerical solution by computing | ||

| # the error, see also the | ||

| # [section about analyzing the solution](https://trixi-framework.github.io/Trixi.jl/stable/callbacks/#Analyzing-the-numerical-solution). | ||

|

|

||

| function initial_condition_sinpi(x, t, equations::LinearScalarAdvectionEquation2D) | ||

| scalar = sinpi(x[1]) * sinpi(x[2]) | ||

| return SVector(scalar) | ||

| end | ||

| initial_condition = initial_condition_sinpi | ||

|

|

||

| # The next step is to define a function of the source term corresponding to our problem. | ||

| # ```math | ||

| # f(u, x, y, t) = - 2 e^{-t} \sin\bigl(2 \pi (x - t) \bigr) \sin\bigl(2 \pi (y - t) \bigr) | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # This function must take the state variable, the spatial coordinates, the time and the | ||

| # equation itself as arguments and returns the source term as a static vector `SVector`. | ||

|

|

||

| function source_term_exp_sinpi(u, x, t, equations::LinearScalarAdvectionEquation2D) | ||

| scalar = - 2 * exp(-t) * sinpi(2*(x[1] - t)) * sinpi(2*(x[2] - t)) | ||

| return SVector(scalar) | ||

| end | ||

|

|

||

| # Now we collect all the information that is necessary to define a spatial discretization, | ||

| # which leaves us with an ODE problem in time with a span from 0.0 to 1.0. | ||

| # This approach is commonly referred to as the method of lines. | ||

|

|

||

| semi = SemidiscretizationHyperbolic(mesh, equations, initial_condition, solver; | ||

| source_terms = source_term_exp_sinpi) | ||

| tspan = (0.0, 1.0) | ||

| ode = semidiscretize(semi, tspan); | ||

|

|

||

| # At this point, our problem is defined. We will use the `solve` function defined in | ||

| # [OrdinaryDiffEq.jl](https://github.com/SciML/OrdinaryDiffEq.jl) to get the solution. | ||

| # OrdinaryDiffEq.jl gives us the ability to customize the solver | ||

| # using callbacks without actually modifying it. Trixi.jl already has some implemented | ||

| # [Callbacks](@ref callbacks-id). The most widely used callbacks in Trixi.jl are | ||

| # [step control callbacks](https://docs.sciml.ai/DiffEqCallbacks/stable/step_control/) that are | ||

| # activated at the end of each time step to perform some actions, e.g. to print statistics. | ||

| # We will show you how to use some of the common callbacks. | ||

|

|

||

| # To print a summary of the simulation setup at the beginning | ||

| # and to reset timers we use the [`SummaryCallback`](@ref). | ||

| # When the returned callback is executed directly, the current timer values are shown. | ||

|

|

||

| summary_callback = SummaryCallback() | ||

|

|

||

| # We also want to analyze the current state of the solution in regular intervals. | ||

| # The [`AnalysisCallback`](@ref) outputs some useful statistical information during the solving process | ||

| # every `interval` time steps. | ||

|

|

||

| analysis_callback = AnalysisCallback(semi, interval = 5) | ||

|

|

||

| # It is also possible to control the time step size using the [`StepsizeCallback`](@ref) if the time | ||

| # integration method isn't adaptive itself. To get more details, look at | ||

| # [CFL based step size control](@ref CFL-based-step-size-control). | ||

|

|

||

| stepsize_callback = StepsizeCallback(cfl = 1.6) | ||

|

|

||

| # To save the current solution in regular intervals we use the [`SaveSolutionCallback`](@ref). | ||

| # We would like to save the initial and final solutions as well. The data | ||

| # will be saved as HDF5 files located in the `out` folder. Afterwards it is possible to visualize | ||

| # a solution from saved files using Trixi2Vtk.jl and ParaView, which is described below in the | ||

| # section [Visualize the solution](@ref Visualize-the-solution). | ||

|

|

||

| save_solution = SaveSolutionCallback(interval = 5, | ||

| save_initial_solution = true, | ||

| save_final_solution = true) | ||

|

|

||

| # Alternatively, we have the option to print solution files at fixed time intervals. | ||

| # ```julua | ||

| # save_solution = SaveSolutionCallback(dt = 0.1, | ||

| # save_initial_solution = true, | ||

| # save_final_solution = true) | ||

| # ``` | ||

|

|

||

| # Another useful callback is the [`SaveRestartCallback`](@ref). It saves information for restarting | ||

| # in regular intervals. We are interested in saving a restart file for the final solution as | ||

| # well. To perform a restart, you need to configure the restart setup in a special way, which is | ||

| # described in the section [Restart simulation](@ref restart). | ||

|

|

||

| save_restart = SaveRestartCallback(interval = 100, save_final_restart = true) | ||

|

|

||

| # Create a `CallbackSet` to collect all callbacks so that they can be passed to the `solve` | ||

| # function. | ||

|

|

||

| callbacks = CallbackSet(summary_callback, analysis_callback, stepsize_callback, save_solution, | ||

| save_restart) | ||

|

|

||

| # The last step is to choose the time integration method. OrdinaryDiffEq.jl defines a wide range of | ||

| # [ODE solvers](https://docs.sciml.ai/DiffEqDocs/latest/solvers/ode_solve/), e.g. | ||

| # `CarpenterKennedy2N54(williamson_condition = false)`. We will pass the ODE | ||

| # problem, the ODE solver and the callbacks to the `solve` function. Also, to use | ||

| # `StepsizeCallback`, we must explicitly specify the initial trial time step `dt`, the selected | ||

| # value is not important, because it will be overwritten by the `StepsizeCallback`. And there is no | ||

| # need to save every step of the solution, we are only interested in the final result. | ||

|

|

||

| sol = solve(ode, CarpenterKennedy2N54(williamson_condition = false), dt = 1.0, | ||

| save_everystep = false, callback = callbacks); | ||

|

|

||

| # Finally, we print the timer summary. | ||

|

|

||

| summary_callback() | ||

|

|

||

| # Now you can plot the solution as shown below, analyze it and improve the stability, accuracy or | ||

| # efficiency of your setup. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| # ## Visualize the solution | ||

|

|

||

| # In the previous part of the tutorial, we calculated the final solution of the given problem, now we want | ||

| # to visualize it. A more detailed explanation of visualization methods can be found in the section | ||

| # [Visualization](@ref visualization). | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| # ### Using Plots.jl | ||

|

|

||

| # The first option is to use the [Plots.jl](https://github.com/JuliaPlots/Plots.jl) package | ||

| # directly after calculations, when the solution is saved in the `sol` variable. We load the | ||

| # package and use the `plot` function. | ||

|

|

||

| using Plots | ||

| plot(sol) | ||

|

|

||

| # To show the mesh on the plot, we need to extract the visualization data from the solution as | ||

| # a [`PlotData2D`](@ref) object. Mesh extraction is possible using the [`getmesh`](@ref) function. | ||

| # Plots.jl has the `plot!` function that allows you to modify an already built graph. | ||

|

|

||

| pd = PlotData2D(sol) | ||

| plot!(getmesh(pd)) | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| # ### Using Trixi2Vtk.jl | ||

|

|

||

| # Another way to visualize a solution is to extract it from a saved HDF5 file. After we used the | ||

| # `solve` function with [`SaveSolutionCallback`](@ref) there is a file with the final solution. | ||

| # It is located in the `out` folder and is named as follows: `solution_index.h5`. The `index` | ||

| # is the final time step of the solution that is padded to 6 digits with zeros from the beginning. | ||

| # With [Trixi2Vtk](@ref) you can convert the HDF5 output file generated by Trixi.jl into a VTK file. | ||

| # This can be used in visualization tools such as [ParaView](https://www.paraview.org) or | ||

| # [VisIt](https://visit.llnl.gov) to plot the solution. The important thing is that currently | ||

| # Trixi2Vtk.jl supports conversion only for solutions in 2D and 3D spatial domains. | ||

|

|

||

| # If you haven't added Trixi2Vtk.jl to your project yet, you can add it as follows. | ||

| # ```julia | ||

| # import Pkg | ||

| # Pkg.add(["Trixi2Vtk"]) | ||

| # ``` | ||

| # Now we load the Trixi2Vtk.jl package and convert the file `out/solution_000018.h5` with | ||

| # the final solution using the [`trixi2vtk`](@ref) function saving the resulting file in the | ||

| # `out` folder. | ||

|

|

||

| using Trixi2Vtk | ||

| trixi2vtk(joinpath("out", "solution_000018.h5"), output_directory="out") | ||

|

|

||

| # Now two files `solution_000018.vtu` and `solution_000018_celldata.vtu` have been generated in the | ||

| # `out` folder. The first one contains all the information for visualizing the solution, the | ||

| # second one contains all the cell-based or discretization-based information. | ||

|

|

||

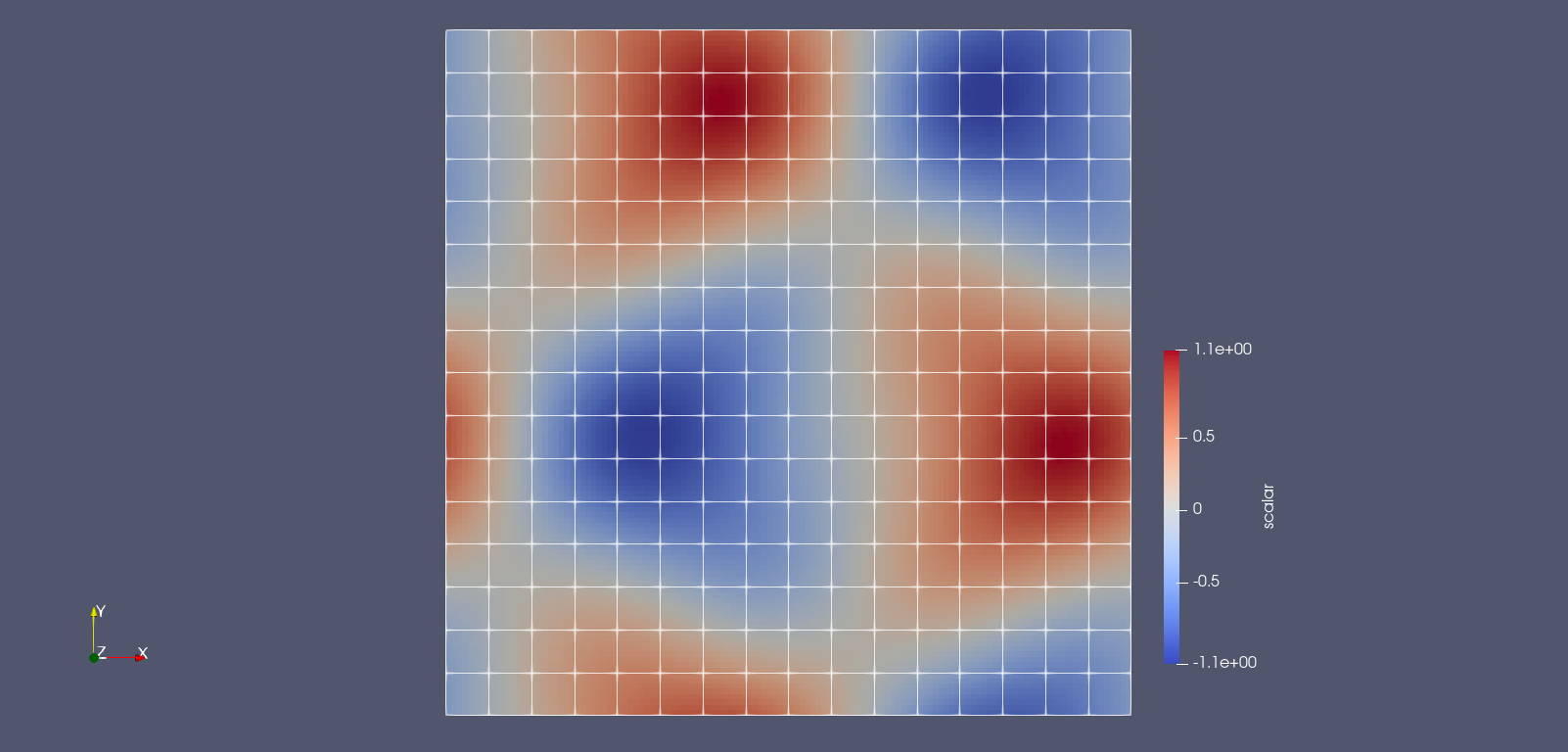

| # Now let's visualize the solution from the generated files in ParaView. Follow this short | ||

| # instruction to get the visualization. | ||

| # - Download, install and open [ParaView](https://www.paraview.org/download/). | ||

| # - Press `Ctrl+O` and select the generated files `solution_000018.vtu` and | ||

| # `solution_000018_celldata.vtu` from the `out` folder. | ||

| # - In the upper-left corner in the Pipeline Browser window, left-click on the eye-icon near | ||

| # `solution_000018.vtu`. | ||

| # - In the lower-left corner in the Properties window, change the Coloring from Solid Color to | ||

| # scalar. This already generates the visualization of the final solution. | ||

| # - Now let's add the mesh to the visualization. In the upper-left corner in the | ||

| # Pipeline Browser window, left-click on the eye-icon near `solution_000018_celldata.vtu`. | ||

| # - In the lower-left corner in the Properties window, change the Representation from Surface | ||

| # to Wireframe. Then a white grid should appear on the visualization. | ||

| # Now, if you followed the instructions exactly, you should get a similar image as shown in the | ||

| # section [Using Plots.jl](@ref Using-Plots.jl): | ||

|

|

||

| #  | ||

|

|

||

| # After completing this tutorial you are able to set up your own simulations with | ||

| # Trixi.jl. If you have an interest in contributing to Trixi.jl as a developer, refer to the third | ||

| # part of the introduction titled [Changing Trixi.jl itself](@ref changing_trixi). | ||

|

|

||

| Sys.rm("out"; recursive=true, force=true) #hide #md |

Oops, something went wrong.